Church Bells and the Whitechapel Bell Foundry

Today is the much heralded and awaited day of Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee Pageant on the River Thames. Ahead of the Royal Barge, Gloriana, and the boat carrying the Queen and her party, The Spirit of Chartwell, will be a belfry barge (the Ursula Catherine) carrying eight church bells specially cast for the Diamond Jubilee Pageant by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in East London. Bells in many of churches along the route of the River Thames’s Jubilee Pageant will be ringing to celebrate the Diamond Jubilee. Many of these churches have been part of London’s rich heritage for hundreds of years.

Each bell on Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee bell belfry barge is named after a senior member of the British Royal Family.

Bell, Name of bell (Donated by) – Musical Note

– Tenor, Elizabeth (Worshipful Company of Vintners) – G#;

– 7th, Philip (Worshipful Company of Dyers) – A#;

– 6th, Charles (Worshipful Company of Glass Sellers) – B#;

– 5th, Anne (Church of St James Garlickhythe) – C#;

– 4th, Andrew (The Bettinson family) – D#;

– 3rd, Edward (Joanna Warrand) – E#;

– 2nd, William (Stockwell family & Worshipful Company of Joiners and Ceilers) – F##; and

– Treble, Henry (Harry) (Nicole Marie Kassimiotis & Worshipful Co. of Musicians) – G#.

(Information from The Royal Jubilee Bells.)

Watch the BBC’s programme Diamond Jubilee Thames Pageant Highlights to see the bells on the belfry barge. There’s a good clear shot of the barge and the bells starting at 29:41.

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

Church bells ringing to celebrate a British monarch is not a modern-day event but has its roots deep in our history. The image below is from the early fourteenth century and shows Henry III (born 1207, died 1272) on his throne beside Westminster Abbey and the Abbey’s bells.

Henry III, by Westminster Abbey and its bells – below is a

Henry III, by Westminster Abbey and its bells – below is a

genealogical table of his descendants, (England, c1307-c1327),

shelfmark Royal 20 A II f.9, © British Library Board.

Church bells were not just used to celebrate coronations and jubilees. My post, Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow, detailed how the church bells of Great Dunmow rung out as Queen Elizabeth I took her royal progress through Essex and Suffolk in the summer 1561. Of course, the primary purpose of church bells in late medieval England was to call a parish’s Catholic community to prayer and so were significant religious objects. Surviving English churchwardens’ accounts from this period often detail the recasting and mending of their church’s bells, bell clappers and even the ropes. Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts are no exception and the accounts have many entries relating to the mending of bells at St Mary the Virgin. Along with mending their bells, the pre-Reformation parish of Great Dunmow also commissioned the casting a new Great Bell in the 1520s from an unnamed bell foundry in London.

The churchwarden accounts detail that between the years of 1527 and 1529, the parishioners of Great Dunmow collected £7 0s 7d for their new Great Bell to be installed in the parish church. This was a highly organised collection instigated by the parish’s pre-Reformation vicar, William Walton, and the local elite. This was the second in a series of seven collections organised by Walton to raise funds for church and religious artefacts. The first was for the church steeple. For the Great Bell collection, the 153 names of house-of-households, their location within Great Dunmow, and the amount each contributed were carefully and meticulously recorded for posterity within the churchwarden’s accounts. Cross referencing the lists of names for each collection with the returns from the 1520s Lay Subsidy Rolls (a tax enforced by Henry VIII) proves that contributions for the new Great Bell were made by nearly every household within the parish – including the parish’s clergy and paupers. Paupers, who were exempt from Henry VIII’s Lay Subsidy tax, paid the unofficial church levy for the parish’s new bell. Many parishioners contributed the equivalent of a day’s pay (4d). The casting of a new church bell was a significant event in the life of this Tudor parish, as can be gleaned from the events surrounding the collection.

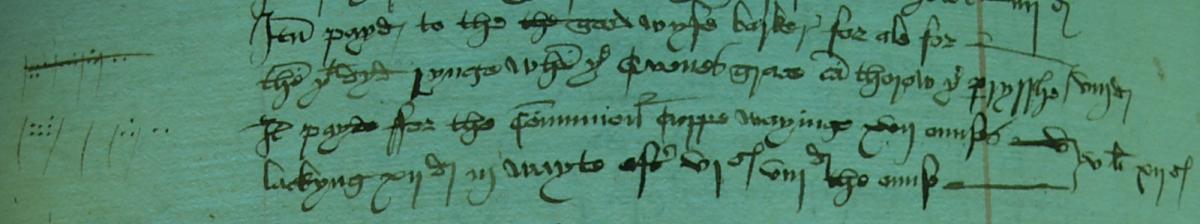

After the entries for the parish collection, the churchwardens’ accounts record a great flurry of activity. The churchwardens and local elite went back and forth to the bell-foundry in London to inspect the casting of their new bell. This incurred some expense as the men claimed their expenses for food & lodgings for their numerous trips from the church’s accounts. Finally the bell was ready to be taken back to the parish church. Whilst the accounts’ purpose was only to list the expenditure and receipts received/made by the parish church, they manage to convey the sense of triumph the entire parish must have felt when the elite were finally able to go to London to ‘fett home the bells’. They paid a staggering £10 to the bellfounder. A further £6 13s 4d was paid out by the parish church ‘for makynge a new flower [floor] in the stepell & a new belframe & new wheles & stoke all owre bells redy to go’. The accounts are silent as to whether or not there was a grand opening ceremony for the new bell – but I rather suspect that there was. The serious shortfall between the amount collected for the bell and the amount eventually paid out was not commented upon in the accounts!

‘Man ringing a church bell with another kneeling behind him; to their right, a priest is at an altar’ from Decretals of Gregory IX with glossa ordinaria (the ‘Smithfield Decretals‘), (France, Last quarter of the 13th century or 1st quarter of the 14th century),

shelfmark Royal 10 E IV f.257, © British Library Board.

The churchwardens’ accounts do not specify the name of the London bell foundry – just that the Great Bell was cast in London. The Whitechapel Bell Foundry, the makers of the Diamond Jubilee Bells, was founded in 1570 during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. However, in recent years a historian has established a link from the Whitechapel Bell Foundry to one Master Founder, Robert Chamberlain, who was active in the first quarter of the fifteenth century. Thus, this Bell Foundry is thought to have been active as early as the 1400s during the medieval period. During the reign of Henry VIII, there can’t have been too many bell foundries in the London and it is likely that all the bell foundries would have been in the east outside the City walls. The noise, smell and risk of fire would have kept the foundries outside populated area and downwind from the prevailing winds coming from the west. There is enough circumstantial evidence to suggest that the pre-Reformation church bells of Great Dunmow were cast in the same bell foundry that cast the 2012 Diamond Jubilee Bells, The Whitechapel Bell Foundry.

London and Westminster in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, anno dom. 1563,

London and Westminster in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, anno dom. 1563,

© British Library Board.

It was these same church-bells which rang out the joy of Queen Elizabeth’s summer progress through the parish over thirty years later on Monday 25th August 1561. Griff Rhys Jones, in the BBC’s new series on the Britain’s Lost Routes, charted Elizabeth’s 1570s progresses from Windsor Castle to Bristol. In his programme, he doesn’t comment on the church bells that must have rung out heralding the Queen’s progress. This is probably more because of the scarce survival of primary source evidence, rather than the pealing of the bells didn’t happen. Great Dunmow is lucky to have any surviving evidence – and this was only because the churchwardens meticulously recorded the expense of 8d paid out to the Good Wife Barker for her ale (Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts – folio 45v.)

There are no surviving church records of the churches in village surrounding Great Dunmow. However, it can be assumed that each village’s church rang out to celebrate the Queen’s progress: Felsted, Little Dunmow, Stebbing, Barnston, Great Dunmow, Little Canfield, Great Canfield, Takeley, and the villages of Hertfordshire surrounding Great Hallingbury. The ringing of the church bells would have been heard by all Elizabeth’s subjects during her progress through the Essex and Hertfordshire countryside.

You may also be interested in the following posts

– Transcripts of Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ account

– Diamond Jubilee

– Queen Elizabeth I’s Progresses through Elizabethan England

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Text in square [brackets] are The Narrator’s transcriptions. Line numbers are merely to assist the reader find their place on the digital image.

The original churchwarden accounts (1526-1621) are in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced.

Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.