Coronation and Diamond Jubilee Goldwork

Have you ever wondered how the beautiful Coronation robes were embroidered with such magnificent goldwork? Or how Kate Middleton’s dress was embroidered so beautifully for her wedding to Prince William? Or how was the amazing goldwork done on robes of the Herald’s of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Pageant? Embroidery on royal or military robes and garments are incredible works requiring great skill and craftsmanship.

The only people able to embroider to such a high level of excellence are, of course, those trained by the remarkable Royal School of Needlework based in Hampton Court Palace.

Whilst I can never claim to being as skilled and as experienced as the embroiders (known as ‘apprentices’) who made the Queen’s Coronation Robes, I can claim first-hand knowledge of how difficult it is to do goldwork embroidery – and how rewarding it is. In 2010-2011, before my dissertation took hold of all my time and attention, I was fortunate enough to attend my first (out of four) embroidery techniques that comprise the Royal School of Needlework‘s Certificate in Technical Hand Embroidery. The technique I choose to be my first (and to date, only technique) was goldwork.

To celebrate the final day of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee weekend, my post today is images of my time at the Royal School of Needlework. I hope these photos convey how technically difficult it is to do goldwork embroidery.

Day 1 – Finding a source for my work. I love the work of William Morris, so chose this pattern

Day 1 – the tiny portion of the amazing William Morris pattern which will form the basis of my work

Day 1 – Framing up. Attaching calico to a “slate” frame (which isn’t made of slate!)

Day 1 – Still framing up – this took hours!

Day 1 – My stitches aren’t very neat but it doesn’t matter because when I’d finished the work, I cut these stitches to remove the work from the frame

Day 1 – My design – this has been “pricked” so I can “pounce” it with white powder made from cuttlefish. The tracing is covered all along the design with

tiny pin-pricks about 2mm apart.

Day 1 – My black silk has been sewn to the calico backing (this took a couple of hours to do). Then the pricked tracing is placed over the black silk and “pounced”. The pounce is made of finely ground cuttle-fish which is then smeared over the tracing so the pounce falls through the tiny holes and leaves an outline on the black silk

Day 1 – All ready for the outline to be painted on.

Day 1 – This was so tricky as I don’t have a steady hand. Using a very fine paint-brush, the outline of the design is painted onto the black silk. It’s a bit too thick in place and too fine in others. When the goldwork is embroidered onto the fabric, it has got to cover all the paint lines so no lines are showing.

Day 1 – All framed, painted and ready to start…

Day 1 – My first bit of padding – a lot of the goldwork has padding underneath the metal threads to raise it up from the surface. This strip has 4 pieces of felt sewn down one on top of the other.

Day 1 – Some of the yellow padding. Most of this work has padding all over it before the gold can be applied.

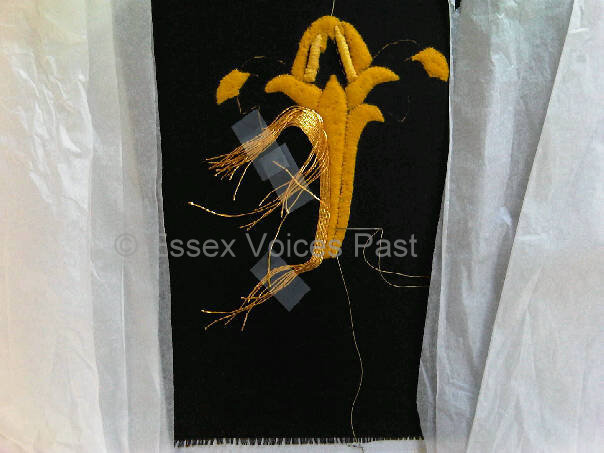

Day 2 – It took me all day to sew the felt padding.

Day 2 – The 2 far out leaves have 2 layers of felt padding. The middle (of 3) long down felt padding is 4 layers, either side of this, it’s 1 layer. The 2 leaves on top/next to the down felt is also 4 layers. The top triangles are 3 layers. The upside down “crown” at the top has 3 layers of tiny circles and the 1 layer of upside down crown.

Day 2 – Urgh. I can’t believe how much fluff is on my lovely black silk!

Day 3 – Soft string padding. This is about 15 strands of thick soft string, heavily waxed with bees wax and then twisted together and tightly sewn down. It was a pain to do!

Day 3 – The beginnings of the 2nd section of waxed soft string

Day 3 – By the end of this day, a lot of my beautiful paintwork had started to brush off. Under the 2nd section of soft string, it had disappeared totally so the yellow lines you can see are from the tacking lines I’ve had to sew in to get back the outline

Day 3 – Lots and lots of tissue paper surround my work so it doesn’t get dirty! I get marks deducted if it is dirty or has wax marks on it. My little pin keep I made myself – it’s so handy.

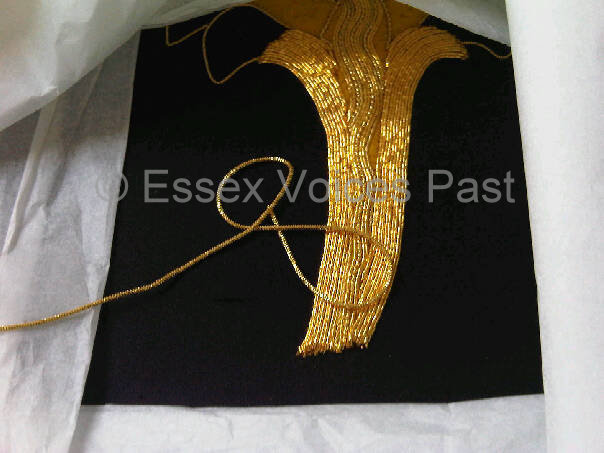

Day 4 – On this day, I got to couch down some Japanese gold thread

Day 4 – All those little “tails” of gold thread had to be taken through the black silk and secured to the back of the picture. Taking the threads through the background fabric is called “plunging”

Day 4 – 2 sides of the stem are now done

Day 4 – The camera doesn’t really show the couching stiches. They are done in a “brick” stitch pattern

Day 5 – Middle section all couched down. Loads of tails that all need plunging

Day 5

Day 5

Day 5 – middle wavy section is three different threads – rocco, Japanese and twist

Day 5 – Bottom of stem have been plunged. Gold threads have been taken through to the back of the fabric by using a lasso of strong button-hole-cotton. The gold thread is threaded through the lasso and then the lasso is pulled tight from the other side of the fabric and with any luck the gold thread will pop through to the other side.

Day 5

Day 5- The back of the work with lots and lots of gold threads

Day 5

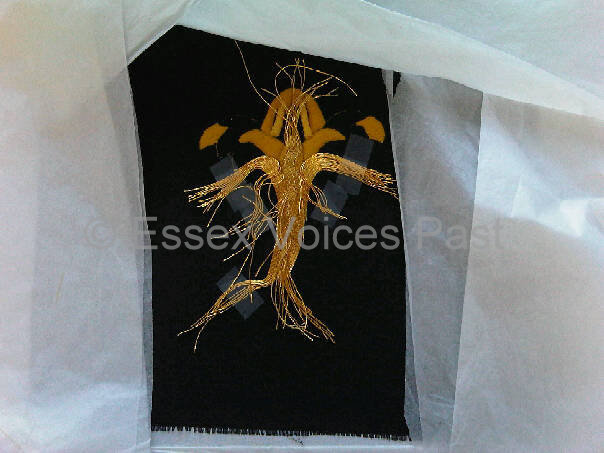

Day 5 – Every thread has been plunged (this took about 4 hours to do them all)

Day 5 – The back of the fabric. Now all these threads had to be securely sewn down in little bundles and the ends snipped off.

Day 6 – back of the fabric – top section of threads have been sewn down. Bottom section awaiting to be done

Day 6 – the only way to sew these little bundles of gold thread down is by using a curved needle. Using a straight normal needle is nearly impossible as the fabric is so taught and the gold threads so thick

Day 6 – Last few bundles to be done

Day 6 – All done

Day 6 – Sewing down the bundles took about 4 hours. Great care has to be taken where each bundle is sewn down to – its got to be on areas that doesn’t have to be sewn over later on. If I got it wrong, I’d be pushing a needle through fabric and the thick bundles of gold thread (ouch!)

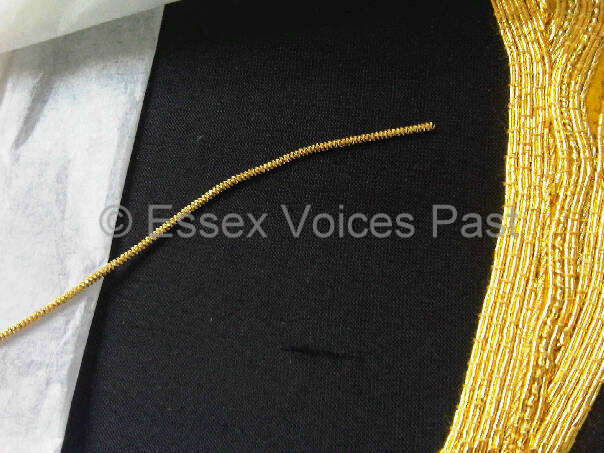

Day 6 – Back to the top of the fabric. I’ve now outlined the left side leaves in pearl purl (or is it purl pearl?) Each leave is indiviually done and I had to work out which line belonged to which leaf

Day 6 – Close up of the pearl purl. My camera shows all the tiny piece of beeswax and fluff from the felt. The felt “leaks” fluff all the time. The pearl purl is sewn down with heavily bees-waxed cottom to make it stronger. It leaves tiny traces of bees-wax behind on the fabric. The next day’s job was to remove all the fluff and bees-wax from my work.

Day 6 – I did the gold swirlie bit on the right of the picture last minutes on day 5. But then I realised I hadn’t done it properly because I tried to loop around in curves at the top of swirlie bit but it just looked awful. So I had to unpick this entire section.

Day 7 – the re-sewn embroidery so that the swirls follow round and round in a spiral. It still wasn’t perfect – too much space between each swirl – but had to do.

Day 7 – both sides are now done in swirlie loops using gold passing thread.

Day 7 – from this close up you can see the swirls are by no means perfect. After I took this photo, the tutor had a good prod and poke arouond and evened up my swirls. The long gold thread hanging off to the left of the picture is pearl purl – used to outline things. Hard work couching it down as you have to pull the waxed thread through the little tiny gaps (pearls). The stitches end up being about 1mm in length

Day 7 – all the pearl is done. And 2 arches of rocco gold thread added to the black part at the top

Day 7 – so the 2 sides aren’t symmetrical! But it’s a flower and not supposed to be symmetrical.

Day 7

Day 7

Day 7

Day 7 – This thread is called bright check. It’s cut into tiny tiny little beads that are then sewn down over the felt

Day 7 – this was to be cut into tiny tiny beads and then sewn down over the remaining yellow felt

Day 7 – half way down the thread is a bead cut from the bright check. The bead is about 2mm in length. That whole tiny area has to be full of hundreds beads with no spaces of yellow left

Day 7 – by the end of each day, my eyes were so tired that I just couldn’t see my goldwork anymore! The tiny gold mark towards the right (by the tissue paper) is where the bright check has very slightly frayed as it’s being cut leaving behind a tiny trace of gold wire and it has bounced onto my work (it brushed off)

Day 7 – as the bright check is cut into beads, it shatters and jumps all over the place. This is the lid of a jam pot so that when the beads jump, it’ll stay within the lid and not disappear. I should have put the lid on tissue paper, instead of straight onto my black silk – everything has to be protected so that no dirty marks are left behind.

Read part 2 of my time at the Royal School of Needlework

and my completed goldwork piece.

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

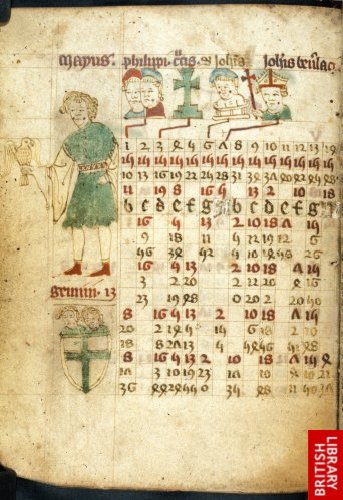

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569),

Title page from the Bishops Bible (London, 1569), © Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

© Essex Record Office, Map Showing the Royal Progress of 1561 (2008)

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

Canaletto’s River Thames on Lord Mayor’s Day 1746, © The Lobkowicz Collections

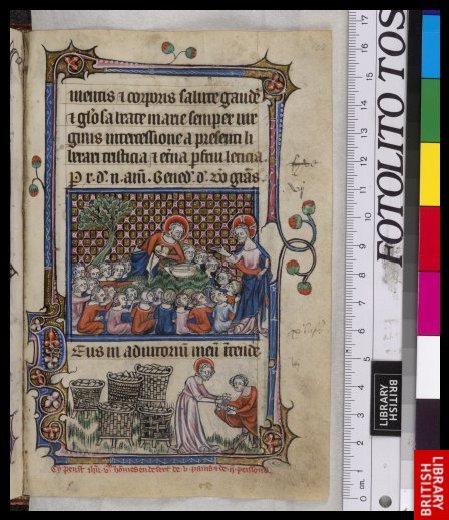

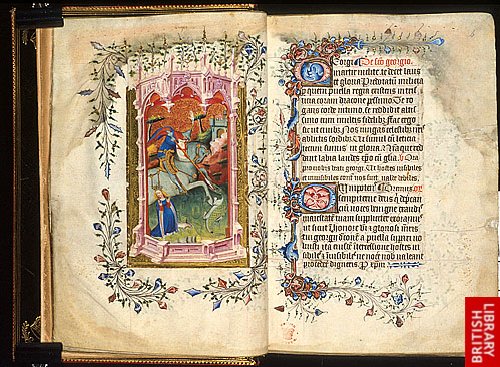

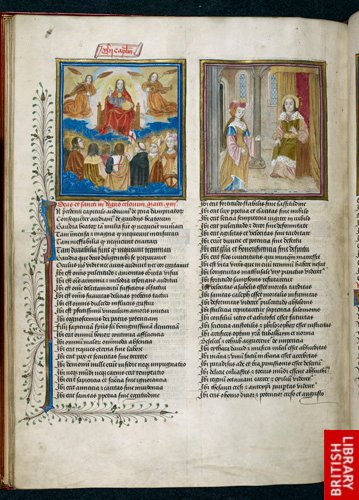

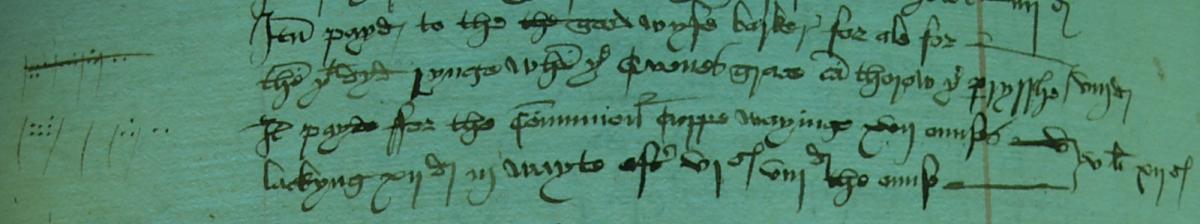

Coronation Oath of Henry VIII with his own annotations (crowned 24 June 1509), shelfmark Cotton Ms. Tiberius D viii, f.89, © British Library Board. (For more information on his changes, see the British Library’s

Coronation Oath of Henry VIII with his own annotations (crowned 24 June 1509), shelfmark Cotton Ms. Tiberius D viii, f.89, © British Library Board. (For more information on his changes, see the British Library’s

Coronation procession of Edward VI along Cheapside, London.

Coronation procession of Edward VI along Cheapside, London.

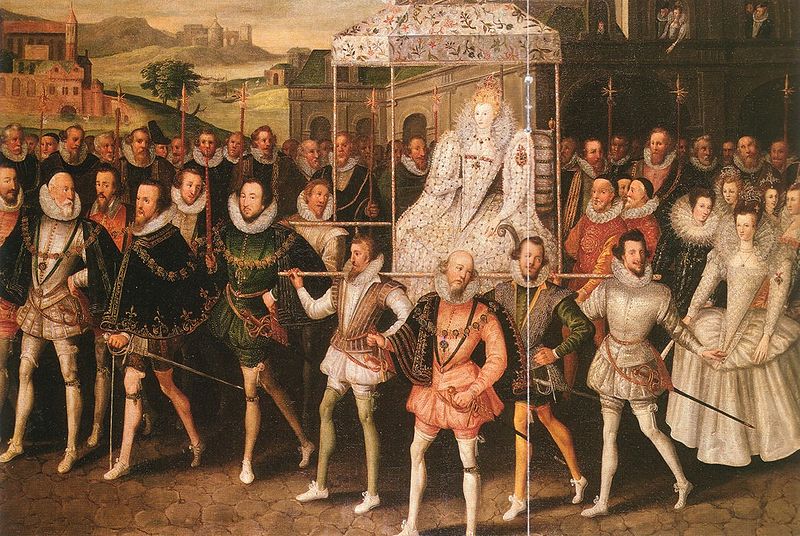

Coronation procession of Elizabeth.

Coronation procession of Elizabeth.