Sturton family of Tudor Great Dunmow and Great Easton

Family members mentioned in the churchwarden accounts include:

– Robert Sturton, vicar of Great Dunmow 1492-1523

– Robert Sturton, church clerk of Great Dunmow

– Robert Sturton

– William Sturton

– Stephen Sturton

– Alexander Sturton

Robert Sturton – vicar of Great Dunmow 1492-1523

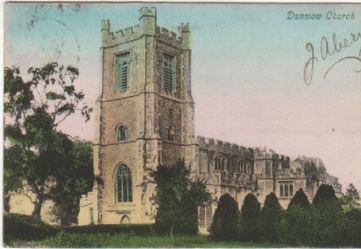

Patron for the living of Great Dunmow: Dean and Fellows of Stoke College, Clare, Suffolk.

Reason for leaving the living of St Mary the Virgin, Great Dunmow, 1523: Resigned

University/degree: Described as ‘master’ in the churchwarden accounts indicating he was an M.A. (Master of Arts). Unknown which university.

1514: possibly the same Robert Stourton (described as a ‘Professor of Theology’ i.e. S.T.P.) who was rector of Long Melford, Suffolk.(1) Long Melford is 28 miles away from Great Dunmow.

19 April 1510: Robert Stourton, clerk, of Great Dunmow, pardoned by Henry VIII.(2)

Died by 1529. The churchwardens’ accounts detail of 53s 4d, a gift from Robert Sturton ‘sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche’. The money was given to the churchwardens by William Sturton.(3) It can be assumed William and Robert were related.

Notes on the Sturton family of Great Dunmow

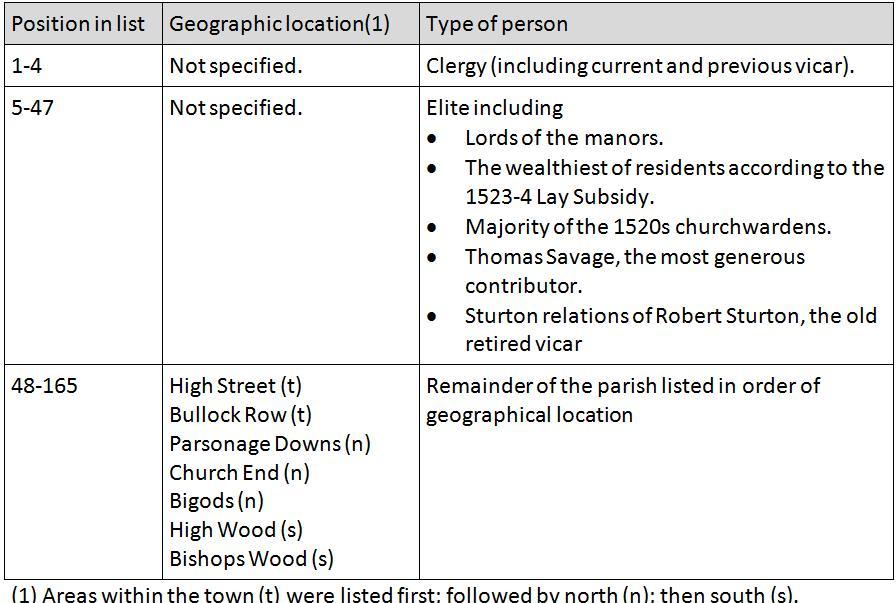

There were many Sturtons within Tudor Great Dunmow. William Sturton was assessed in the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy for goods to the value of £40.(4) Two Robert Sturtons were also assessed, both with goods to the value of 20s. Stephen Sturton was also assessed. As the clergy were exempt from the Lay Subsidy, this implies that, including the vicar, there were three Robert Sturtons in Great Dunmow. Robert Sturton, the church clerk from the start of the churchwardens’ accounts until the mid-1540s was one of them. Throughout the Henrician churchwardens’ accounts, his wife received payment from the churchwardens for washing the church’s linen.

The only Sturton will to have survived is Alexander Sturton’s will of 1553. Alexander Sturton, of Clopton Hall, bequeathed money to the children of Stephen Sturton, Thomas Sturton, Robert Sturton and William Sturton (all deceased).(5) This suggests that Alexander Sturton was possibly the son of one of the three Robert Sturtons. Clopton Hall was one of Great Dunmow’s medieval manors.

Two William Sturtons from Great Dunmow were educated at Cambridge University. In 1526 William Sturton, aged 18, a scholar from Eton, of Dunmow, Essex, matriculated at Kings. He became a fellow of Kings College 1529-30, ordained Deacon of Lincoln 1530, and Precentor of Kings College 1541-9.(6) The other William Sturton of Great Dunmow matriculated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge in 1564 aged 16 and was the son of Alexander Sturton.(7)

Thus, there is both circumstantial and solid evidence linking these Sturtons together. The evidence demonstrates they were an elite and well-established family. It is likely they were related to the Lord Stourtons of Stourton, Wiltshire.

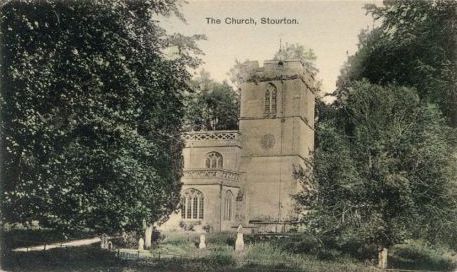

In the early fifteenth century, Sir John Moigne held the Manor of Great Easton along with the advowson of the village’s church. Sir John’s heirs were his daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, Sir William Stourton. Sir William was presented to the rectory of Great Easton on the 3rd January 1408. Sir William’s Inquisition Post Mortem took place in Great Dunmow in the regnal year I Henry V. (1413-4). His son, John Stourton (who later became 1st Lord Stourton), was presented to Great Easton’s rectory on 5th January 1427. Throughout the fifteenth century and early sixteenth century, the House of Stourton held the Manor of Great Easton, and also the Manor of Blamster in the same village. Great Easton remained part of the Stourton estate until William, 7th Lord Stourton, sold the Manor and advowson in 1536.(8) Great Easton is a village 2.5 miles from Great Dunmow.

Great Easton, Essex, 2012

Great Easton, Essex, 2012

© Essex Voices Past 2012.

Henry VIII’s Pardon Rolls of 1509-14 documented William Stourton, knight, Lord Stourton, as the tenant of the manor of Estaynes ad Montem, Essex [Great Easton].(9) It has been suggested the true phonetic spelling of the name ‘Stourton’ is ‘Sturton’.(10) The scribes who wrote the churchwardens’ accounts used phonetic spellings for many names and places.

Therefore, it is probable Robert Sturton, vicar of Great Dunmow, and the other Sturtons of Great Dunmow, were distant relations to the House of Stourton.

Footnotes:

1) William Parker, The History of Long Melford (1873), 35.

2) J.S. Brewer (ed.), ‘Henry VIII: Pardon Roll, Part 1’ in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1: 1509-1514 (1920), 203-216, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=102632 .

3) Great Dunmow, Churchwarden accounts (1526-1621), Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1, fo.7r.

4) Hundred of Dunmow: Calendar of Lay Subsidy Rolls (1523-4), E.R.O., T/A427/1/1.

5) Will of Alexander Sturton (1553), E.R.O., D/ABW 33/226.

6) John Venn, ‘William Sturton’ in Alumni Cantabrigienses Part I Volume IV (Cambridge, 1927), 181.

7) Venn, ‘William Stoorton’. in Alumni Cantabrigienses Part I Volume IV, 181.

8 ) Lord Mowbray, Segrave, and Stourton, The history of the noble house of Stourton (1899), 105-7 and 151.

9) J.S. Brewer (ed.), ‘Henry VIII: Pardon Roll, Part 3’ in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1: 1509-1514 (1920), 234-256, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=102634 .

10) Mowbray, Stourton, 2.

Postcards displayed on this page in the personal collection of The Narrator.

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– Great Dunmow’s Medieval manors

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

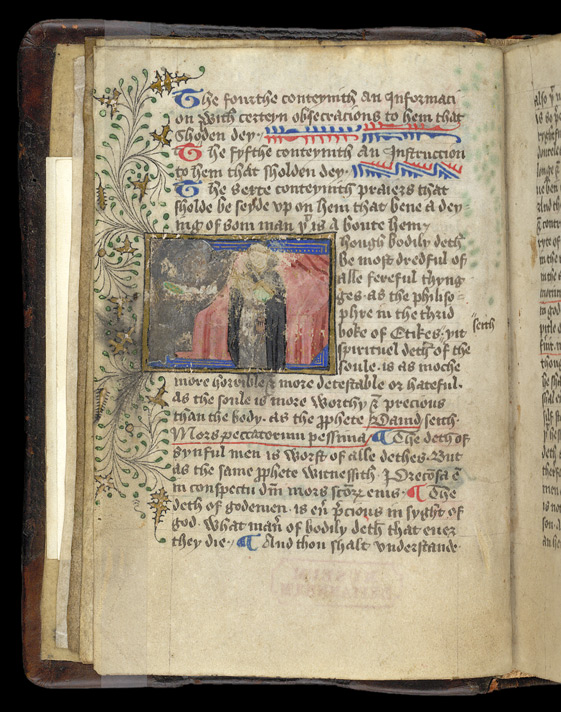

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3).

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3). A priest giving communion to a sick man,

A priest giving communion to a sick man,