Blacksheep Sunday: Witchcraft and witches – Part 1

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

The county of Essex, England, is notorious for the high number of sixteenth and seventeenth century witchcraft trials which took place at its regular county Assizes (courts) in Brentwood, Chelmsford and Colchester. There is not a consensus of opinion why it was that Essex had such a high number of these witchcraft trials. It could be simply be that a higher number of trial records survive in Essex then in other counties, thus distorting the figures. Other reasons could include the fact that Essex seemed to be particularly unlucky in having at least two very active ‘witchfinders’ who took it upon themselves to root out so-called ‘witches’. These ‘witchfinders’ included the magistrate of St Osyth, Brian D’Arcy, who in 1582 contributed to at least 10 women being tried and hanged for murder; and Matthew Hopkins, the infamous ‘Witchfinder General’ who rampaged through the eastern counties of England in 1645.

Frontispiece from Matthew Hopkins’ The Discovery of Witches (London, 1647) Shelfmark: E.388.(2) © The British Library Board

The mandate for these trials were the Elizabethan witchcraft statute of 1563 (an “Act against Conjuracions Inchantments and Witchecraftes” (1)) and the harsher 1604 Jacobean witchcraft act (an “Act against Conjuration Witchcrafte and dealinge with evil and wicked Spirits(2)”) which was finally repealed in 1736. Contemporary people throughout England and Europe were fascinated by witches and the perception of malicious harm caused to both people and animals by people practising witchcraft. It seems that all levels of society believed in “witches”, from King James I of England (who, as James VI of Scotland, wrote “Daemonologie” (1597), an influential treatise on the subject), to the victims and witnesses who reported their former friends and neighbours as witches to the authorities.

Today, these witchcraft cases are much studied by eminent historians and anthropologists, for example, Alan MacFarlane(3), Keith Thomas(4), Robin Briggs(5) and James Sharpe(6). Historians consider both official public records such as the Assizes and Quarter Sessions accounts, along with “unofficial” accounts, such as contemporary treatises and pamphlets. Studying these records can provide a picture of life, relationships and tensions within sixteenth and seventeenth century communities of England. An explanation for witchcraft that modern historians such as Thomas and MacFarlane have put forward is that the accusations occurred when there were disputes between people. Thomas observed: “[this was a] tightly-knit, intolerant world with which the witch had parted company. She was the extreme example of the malignant or non-conforming person against whom the local community had always taken punitive action in the interests of social harmony.”(7) He further remarks that when there was a breakdown of the mutual help that many English villagers relied on during this period, accusations of witchcraft often followed.(8)

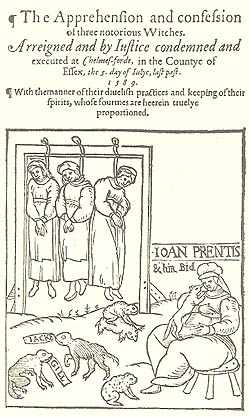

The apprehension and confession of three notorious witches. Arreigned and by iustice condemned and executed at Chelmes-forde, in the Countye of Essex, (Joan Cunny, Joan Upney and Joan Prentice) (1589)

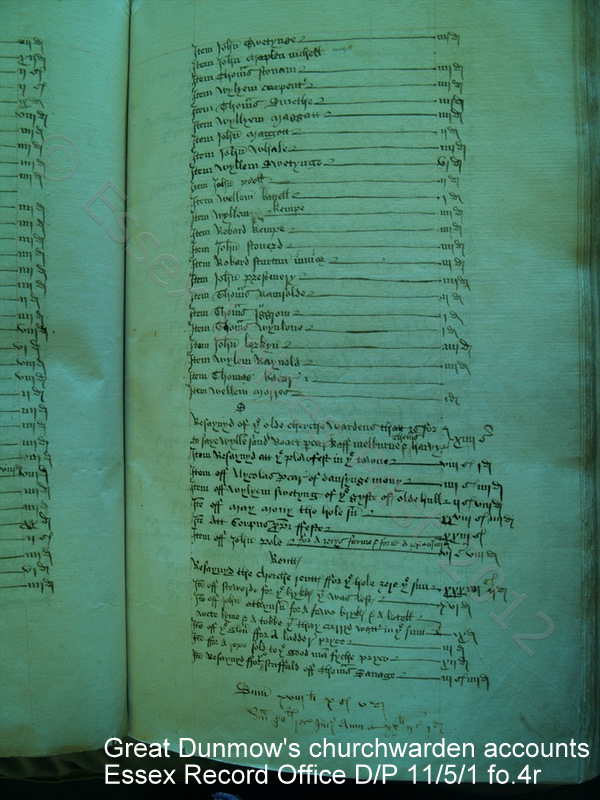

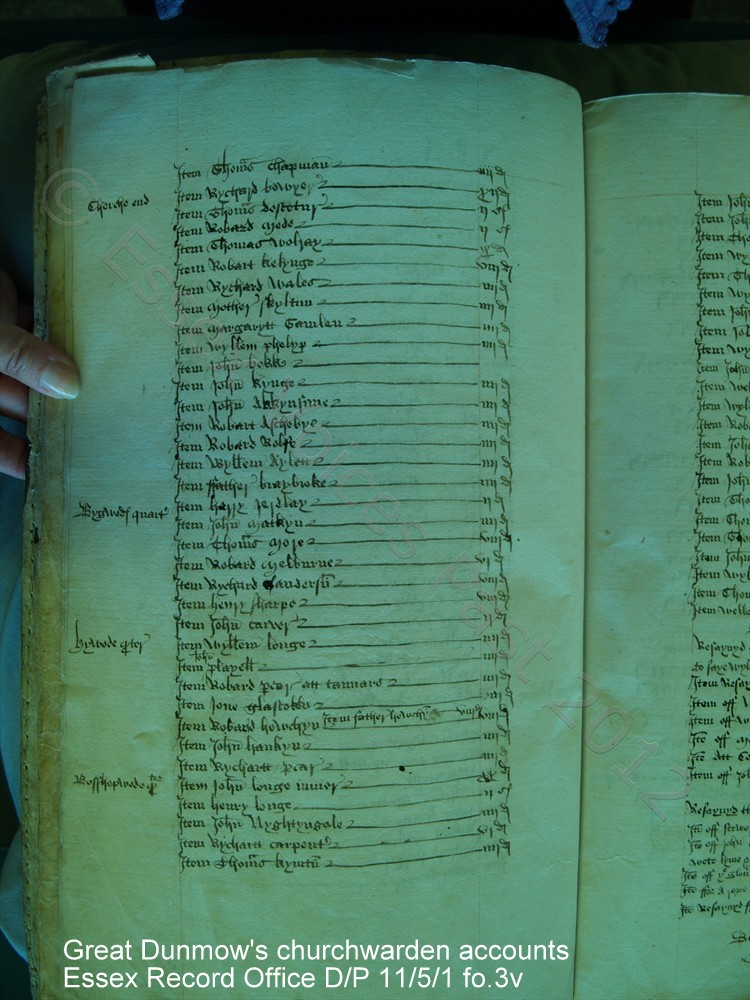

This breakdown of previously good, neighbourly relationships can be observed by analysing Great Dunmow’s Lay Subsidy returns, the churchwardens’ accounts, together with Assize trial records to determine how neighbours Robert Parker and John Prestmary fell out to such an extent that the cry of ‘witchcraft’ was heard in Great Dunmow. The first Prestmary husband and wife witches to appear in the court records are in 1567:

Alice Prestmary

“on 1 February 1567 Alice PRESTMARYE of Great Dunmow, wife of John PRESTMARYE spinster, bewitched Edward Parker son of Robert Parker “tanner”, putting him in peril of his life, so that his life is despaired of.” (9)

She pleaded not guilty but was found guilty. The Judgement was according to the Statute (which meant 1 year in prison with quarterly appearances of 6 hours in the pillory). However, she died of the plague in prison on 7 May.

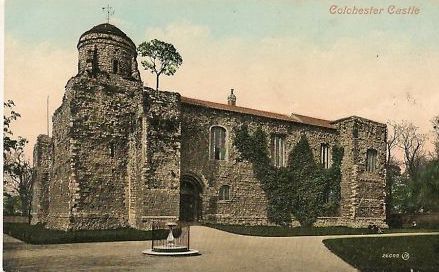

“INQUISITIONS: Taken on 7 May 9 Eliz., at Colchester, before John and rob. Myddeton, coroners for the town of colchester, on view of the body of Alice PRESTMARY a prisoner in Colchester Castle. the jurors say that she languished for a month of on illness called `a fever’ from 1 to 6 May and then died. Visitation of God.”(10)

Colchester Castle, Tudor county gaol and prison for many Essex women (and men) accused of witchcraft

John Prestmary

John Prestmary was Alice’s husband. Sadly, he committed suicide shortly before his wife’s trial. The records are very sparse and we can now only guess why he was driven to such an act.

“INQUISITIONS: Taken on 1 February 9 eliz., at Great dunmow, before tho. Knott, coroner, on view of the body of John PRESTMARYE of Great Dunmow lab. aged 60 years. The jurors say that John on 30 January hanged himself from a `walnute tree’ in his garden with a halter. Felo de se.” (11)

Alice’s husband’s suicide (the felo de se in the inquisition records) would probably have been taken as further prove that Alice was a witch. “In England, Satan was frankly cited as an accessory in case of felo-de-se and homicide, and the coroner’s inquisition taken upon view of the body of a suicide formerly followed the wording of the indictment for murder, the jurors presenting that the deceased ‘not having God before his eyes, but being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil, did murder himself’”(12)

The Parkers and Prestmarys had been neighbours since at least the 1520s. However, forty years later, Alice was accused of bewitching Robert Parker’s child, Edward. Part 2 of this story explores the Parkers and the Prestmarys of Great Dunmow and examines the circumstances surrounding the first Prestmary husband and wife tried for witchcraft.

Note on the Prestmary spelling

So far in the records I have seen the name spelt as below. For uniformity my posts (unless quoting directly from primary sources) will use the most consistent spelling – ‘Prestmary’.

- Prestmary

- Prestmarye

- Prestmery

- Prestmarie

- Presmary

- Presmarye

- Presmere

- Presmere

- Preistmarye

- Prestmare

- Preasmary

Footnotes

1) MacFarlane, A; Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England: A regional and comparative study; (1st Edition,1970) p14.

2) Ewen, C L’Estrange; Witch Hunting and Witch Trials : The Indictments for Witchcraft from the Records of 1373 Assizes held for the Home Circuit A.D. 1559-1736; (1929) p19.

3) MacFarlane, A; Witchcraft in Tudor and Stuart England (2nd Edition,1999).

4) Thomas, K; Religion and the decline of Magic (1991).

5) Briggs, R; Witches and Neighbours: The Social and Cultural Context of European Witchcraft (2nd edition, 2002)

6) Sharpe, J., Witchcraft in early Modern England; The bewitching of Anne Gunter: A horrible and true story of football, witchcraft, murder and the King of England; English witchcraft 1560-1736; Volumes 1 to 6 (Gen Ed)

7) Thomas, K; (1991), Religion and the Decline of Magic; p632

8) Thomas, K; (1991), Religion and the Decline of Magic; p662

9) Calendar of Essex Assize File [ASS 35/9/2] Assizes held at Brentwood (13 March 1567), Essex Record Office, T/A 418/11/5.

10) Calendar of Queen’s Bench Indictments Ancient 619, Part I, (1567), Essex Record Office, T/A 428/1/14A

11) Calendar of Queen’s Bench Indictments Ancient 617,Part I, (1567), Essex Record Office, T/A 428/1/12A

12) Ewen, C L’Estrange; Witchcraft and Demonism (1933), p87-88.

Postcards displayed on this page in the personal collection of The Narrator.

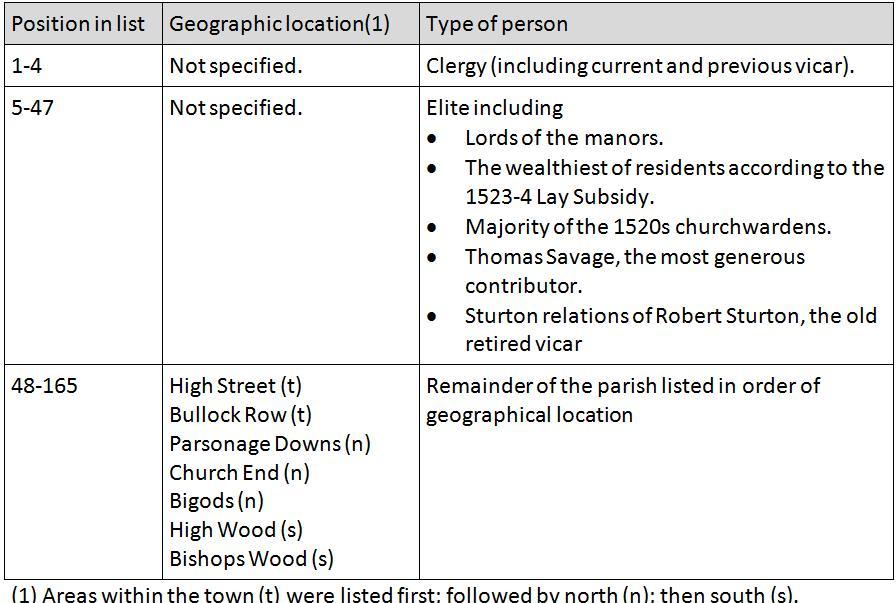

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

If you want to learn more about Essex’s witches, then you may be interested in my online course about the Witches of Elizabethan and Stuart Essex. Click the “Learn More” button below for full details.

| Post Updated: April 2020 Post Created: 2012 © Kate J Cole | Essex Voices Past™ 2012-2020 |

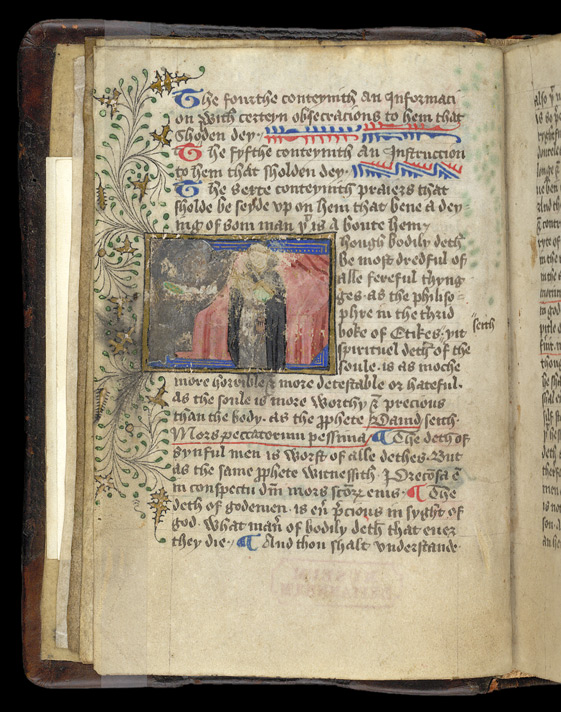

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3).

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3). A priest giving communion to a sick man,

A priest giving communion to a sick man,