The only Welshman in the village: A Tudor conundrum

During my research of Great Dunmow’s Tudor past, I have come across quite a few mysteries and conundrums. One such mystery is that of Griffith Ap Rice, a Welshman who appears in Great Dunmow’s records in the 1520s and 1530s. I have a lot of circumstantial evidence as to who he ‘might’ be. But no hard concrete evidence as to who he really was. More to the point, exactly what was a lone Welshman doing in the relatively sleepy backwaters of a small East Anglian town nearly 40 years after the Battle of Bosworth brought many soldiers out of their native Welsh hamlets and villages and into England? Like a medieval ghost, our Welshman flits through the records of Great Dunmow every now and again; and only the mere tantalising hint that he existed can be glimpsed in the records.

So here he is, my unfinished research on Griffith ap Rice, the only Welshman in Tudor Great Dunmow. To help with reading my post, I have Anglicised his name in my commentary but have kept to the many various original spellings for when he appears in the records.

Who was Griffith ap Rice?

He was a stray in Great Dunmow’s Tudor records during the reign of Henry VIII and can be counted as one of the “middling sort” of the town – one of the wealthy elite of the town, but not quite in the upper echelons of the town’s society – and the only person in Tudor Great Dunmow with a definite Welsh name.

Documents/Records where Griffith ap Rice is recorded?

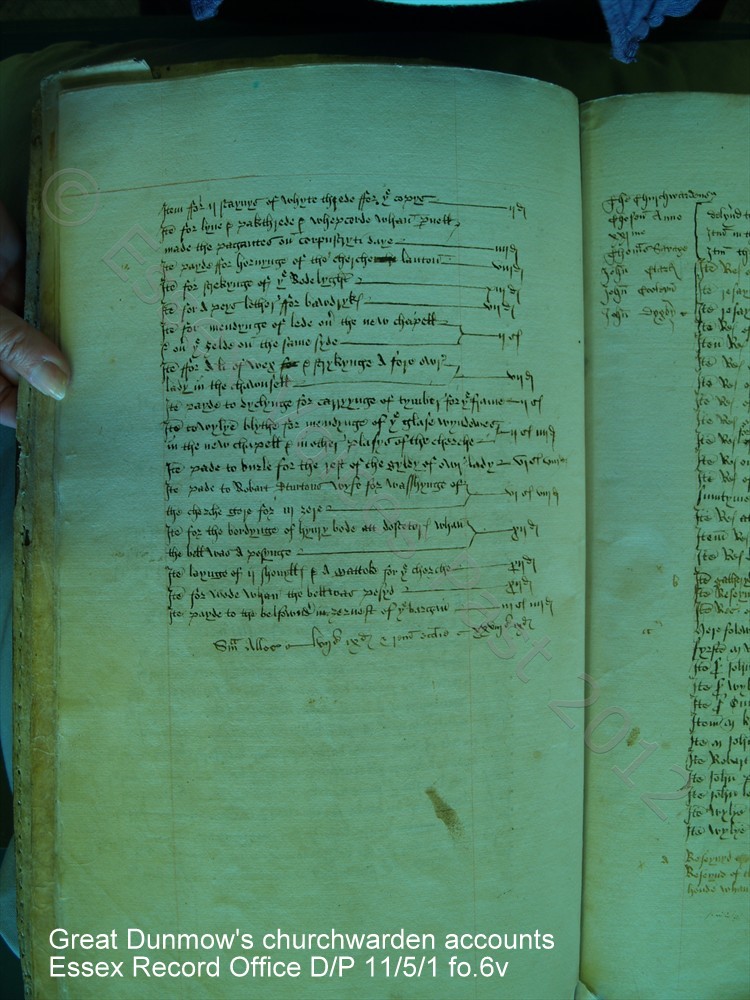

![]()

1523 – Great Dunmow’s lay subsidy returns. Grephyd Ap Rice was assessed for goods to the value of 20 shillings and paid tax of 12d. He was the joint 37th wealthiest man (out of 139 households) listed in the lay subsidy returns. My post on Henry VIII’s Lay Subsidy describes this levy – a tax to raise money for the king’s wars with France.

1525-6 – Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts : Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1 folio 2r. Collection for the Church Steeple – Grefyn Apryce paid 2s (average was 4d per household). Griffith ap Rice’s entry is the 16th entry in the list of the whole parish. The list was written-up into the churchwardens’ account book in strict social-hierarchical order – thus the parish’s clergy were first on the list, followed by the elite, then the middling sort. The person who contributed the most to the collection, Thomas Savage, who gave £3 6s 8d, is listed at number 24 – lower down than Griffith ap Rice. ap Rice’s entry is amongst the entries for the middling sort.

1525-6 – Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts : Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1 folio 2r. Collection for the Church Steeple – Grefyn Apryce paid 2s (average was 4d per household). Griffith ap Rice’s entry is the 16th entry in the list of the whole parish. The list was written-up into the churchwardens’ account book in strict social-hierarchical order – thus the parish’s clergy were first on the list, followed by the elite, then the middling sort. The person who contributed the most to the collection, Thomas Savage, who gave £3 6s 8d, is listed at number 24 – lower down than Griffith ap Rice. ap Rice’s entry is amongst the entries for the middling sort.

1527-9 – Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts – collection for the Church Bell:

Grefythe Apryce paid 14d (average 2d or 4d per household). In this complete list of all the heads of houses in Great Dunmow, Griffith ap Rice is listed in 15th place – amongst all the middling sort of the town. In this list, a complete list of the entire town, heads-of houses from 19th place onwards are listed alongside the location of their dwelling-place in the town. So, for example, John Swetynge is listed as living in Windmill Street, and Nycolas Aylett as living in the High Street. However, the first 18 heads-of-houses listed do not have their location in the town named. It is as if these people are so important that the church did not need to make a note of these people’s houses. Griffith ap Rice’s name is within this portion of the list and so his precise location in the town is unidentified but the lack of location gives firm testimony that he was an important person in the Tudor town of Great Dunmow.

1529-30 – Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts – collection for Church Organs:

Gryffeth Appryce paid 12d (average 2d or 4d per household). In this collection, he is detailed 8th in the list of contributors towards the church’s organs – immediately under the town’s elite and amongst the town’s middling sort.

He did not contribute towards the church’s collection for the ‘New Guild’ (1532-3) – but was almost certainly dead by time of this collection.

1532-3: Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts : Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1 folio 17v. Gift of money from Griffythe Appryce £3 6s 8d. ‘Ite[m] resayvyd of John Honwyke [churchwarden] & John ffost[er] off gefte of Greffythe Appryce iijli vjs viijd’ This sum of money was probably a bequest left to the church by Griffith ap Rice in his will. In the nearly ten years between his entry in the 1523 Lay Subsidy returns, and his entry in the churchwardens’ accounts for his bequest at the time of his death, his wealth increased from owning goods to the value of 20 shillings (or £1) to leaving in his will a sum of money over three times that amount.

1532-3: Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts : Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1 folio 17v. Gift of money from Griffythe Appryce £3 6s 8d. ‘Ite[m] resayvyd of John Honwyke [churchwarden] & John ffost[er] off gefte of Greffythe Appryce iijli vjs viijd’ This sum of money was probably a bequest left to the church by Griffith ap Rice in his will. In the nearly ten years between his entry in the 1523 Lay Subsidy returns, and his entry in the churchwardens’ accounts for his bequest at the time of his death, his wealth increased from owning goods to the value of 20 shillings (or £1) to leaving in his will a sum of money over three times that amount.

Apart from the instances noted above, Griffith ap Rice does not appear anywhere else in Great Dunmow’s surviving records for the period. Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts start in 1525 and numerous local people are named in these accounts – names of churchwardens, the elite of the town, the church’s lay-officials, local builders, the church’s tenant farmers, and labourers appear throughout the accounts – but he is not mentioned anywhere else in the accounts, nor, despite his wealth, was he named as being any of the town’s Lords of Misrule. Is this unwitting testimony that as a Welshman, even though he was fairly wealthy and one of the middling-sort of the town, he was not allowed to take on one of the more prestigious roles within this Tudor parish? Or am I reading too much into him being totally missing from the rest of the churchwardens’ accounts?

Do we know Griffith ap Rice’s vital details?

Birth: No later than 1502 (because of entry in 1523 in Lay Subsidy). I do not know the minimum age for contributing towards this tax levied by Henry VIII so am assuming that 21 was the minimum age. The subsidy was imposed on the heads of households – so by 1523, Griffith ap Rice was the head of his house. This puts his date of birth more likely to be in the mid to late 1400s.

Marriage: Do not know if he was married or if he had children. Great Dunmow’s marriage records start in 1558 and baptisms start in 1538 – so theses records are too late to discover details about him or a possible wife and children. However, it would seem that ap Rice either was unmarried at the time of his death, or died a childless widower. His financial bequest to the parish church in Great Dunmow was physically handed over to the church by the churchwardens, John Honwyke & John ffost[er], not by a member of his family. Elsewhere in the churchwardens’ account, monetary bequests of money are stated to have been handed over by the dead man’s widow or kinsfolk to the church. Also, the name “ap Rice” disappears totally from the churchwardens’ accounts: the name is not detailed in any further parish collections, nor in any other context within the accounts.

Death: 1532/1533. We know this because of the gift of money entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts and the fact that he is not named in the later church collections raised by Great Dunmow on the entire parish. Great Dunmow’s burial records start in 1558.

What was Griffith ap Rice’s wealth?

Wealth: Paid more than the average donation to each of Great Dunmow’s church collections levied on the entire parish – he is listed with the three (nearly) yearly collections to buy items for the church and is consistently listed in the section containing the “middling-sort” of the town. In the town’s Lay Subsidy returns, he was the equal 37th wealthiest man in Great Dunmow (out of 139 recorded households – not including the clergy and paupers). So in terms of wealth, he was in the top 20-25% of the town.

Will: No surviving 1530s ap Rhys will in Essex Record Office, London Metropolitan Archives, or National Archive. ERO has 10 surviving wills from Great Dunmow for the period 1520s to 1546. LMA is missing ALL wills for the London Consistory Court from 1521 to approx 1539. The entire registers are missing and have been probably since the Reformation – see my post on Reformation Wills and Religious Bequests. Great Dunmow was in the archdeaconry of Middlesex but many nearby towns and villages (for example, Maldon and Chelmsford) were in the archdeaconry of Essex. If a testator had land in two archdeaconries, then the will would be proved in London Consistory Court. Lay subsidy and parish collections show that ap Rice was of the middling-sort (top 20-25% in terms of wealth), so very possible that he had land not just Great Dunmow but possibly in two archdeaconries. So very likely that his will has not survived as it would be in the missing registers.

That’s it! That’s all I have on my Tudor conundrum –

Griffith Ap Rice, the only Welshman in the village. Who was he?

Can a link to another person help?

With the little detail I have on Griffith ap Rice, could researching another person help me work out who he was? To do this, I looked at two Tudor people, Lord Stourton, 7th Baron Stourton and Agnes ap Rice.

Kinsfolk/Linkage to Agnes Rice (aka ap Rhys)

William Stourton, 7th Baron Stourton (c1505-1548) of Wiltshire had an ‘association’ (as a Victorian book on the Stourtons so prudishly put it) with Agnes Rice (born circa 1522, died 1574) – who was also known as Agnes ap Rhys. Lord Stourton bigamously married her whilst his first wife was still alive. On his death in 1548, Lord Stourton left his considerable fortune to Agnes and their child, but his will was ultimately overturned because of the bigamous nature of their marriage, and the small fact that his legal heir was his eldest son, Charles, by his first (legitimate) marriage.

Although the Baron Stourtons’ family home was in Wiltshire, they owned the ecclesiastical living of Great Easton in Essex (about 3 miles from Great Dunmow) and their names are present in numerous records in both Great Dunmow and Great Easton from the 1300s onwards. (See Lord Mowbray, Segrave and Stourton, C., The history of the noble house of Stourton (1899)). This 1899 book states that the evidence seemed to point that the Lord Stourtons did not live in Great Easton/Great Dunmow. However, my research shows that the National Archive holds a couple of records proving that, even if the 7th Baron was not living in Great Easton, he had considerable interests in the village and legally defended those interests in the courts of law of the time when the Abbott at nearby Tilty Abbey tried to infringe on his interests at the church in Great Easton.

There is no hard evidence that William, Lord Stourton, nor Agnes ap Rice lived in (or visited) Great Easton but it is a great coincidence that in the town just 3 miles away was a Griffith ap Rice, who, although not the wealthiest of townsfolk, was amongst the middling-sort. Great Easton had very strong Tudor connections to Great Dunmow – the latter seeing itself as the “mother” town to all the nearby villages – especially when celebrating the Catholic ritual year such as May Day and the community feast-day of Corpus Christi when people from outlying villages came into Great Dunmow to make merry and celebrate. Moreover, there is a further link between Great Easton and Great Dunmow and the elite of the two villages. The vicar of Great Dunmow between the 1490s and 1520s was a Robert Sturton. The town of Great Dunmow was stuffed full of elite Sturtons (including two other men named ‘Robert Sturton’), and, although only one Sturton will has survived from the 1550s, I can loosely connect this vicar to all these Great Dunmow Sturtons (ie they ‘have’ to be related to each other but, because he was an unmarried cleric without children, I’m not sure exactly how). So this was a long established elite family with various members living in some of the medieval manors of Great Dunmow and one of their own, a Cambridge University educated man, was the town’s vicar. Therefore, there is a lot of circumstantial evidence linking the Lord Stourtons of Wiltshire to Great Dunmow’s Sturtons and that these Essex Sturtons were a lesser branch of the Wiltshire Stourtons – probably connected in some-way during the 1300s or 1400s. My post on the vicars of Great Dunmow gives more details about the Sturton/Stourton connection.

So why are the links between Great Easton/Great Dunmow and the Sturtons/Stourtons so important when trying to discover who Great Dunmow’s only Welshman in the village was? To answer this, we have to look at the genealogy of the mistress (or bigamous wife) of William Stourton, 7th Baron Stourton, Agnes ap Rice.

Agnes ap Rice’s parents were Rhys Ap Griffith (1508–1531) and Catherine Howard (daughter of the Duke of Norfolk) – making Agnes the first cousin of Henry VIII’s queens, Catherine Howard and Anne Boleyn. Her father, Rhys ap Griffith (executed by Henry VIII for treason in 1531) was the son of Gruffydd ap Rhys (c1478–1521). Gruffydd ap Rhys was a prominent knight firstly at the court of prince Arthur and then at the court of Henry VIII and he was at the Field of the Cloth of Gold with Henry VIII.

His father was Rhys ap Thomas (1449–1525) who was a fierce supporter of Henry Tudor at the battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. There is a still current rumour that it was this Rhys ap Thomas who cut down and killed Richard III on the battlefield with a pole-axe (boo, hiss!) When Henry Tudor became King Henry VII, Rhys ap Thomas, the slayer of the anointed king of England, became the most powerful man in south Wales.

If you’ve managed to follow these Welsh family with their patronymic names, well done! I got very lost working out who was who – so I had to draw up a very rough and ready family tree.

Was Agnes ap Rice a kinswoman of Great Dunmow’s Griffith ap Rice?

The possible links between Great Dunmow’s Griffith ap Rice and Agnes ap Rice are tantalising. With the Welsh patronymic naming system, was our Griffith ap Rice’s father Rhys ap Griffith? But if his father was thus named, then our Griffith wasn’t Agnes’ brother as Agnes’ brother, Griffith ap Rice, is well documented in the records. So if they are related, the links would be further back in time then the 1520s.

I’m so near, but so far from working out who Great Dunmow’s only Welshman in the town really was.

Had our Griffith ap Rice (or his father) come to

East Anglia after the Battle of Bosworth with Henry Tudor’s Welsh army

alongside their kinsman Rhys ap Thomas

(Or am I, as a historian, getting way too much carried away with myself!)

This is still very much work in progress, and maybe one day I’ll discover who Tudor Great Dunmow’s Welshman was.

Postscript

Agnes ap Rice, in her own right was a very interesting character. After the death of Lord Stourton, 7th Baron Stourton, she went on to marry Sir Edward Baynton. There is a very interesting account on the Bayntun History website of the death in 1564 of Agnes’ and Edward’s only living son, William, allegedly by witchcraft .

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

You may also be interested in the following

– Reformation Wills and Religious Bequests

– Transcripts of Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts – 1526-1621

– Medieval Catholic Ritual Year

– Tudor local history

– Building a medieval church steeple

– Henry VIII’s Lay Subsidy 1523-1524

– Images of Medieval Funerals

– The dialect of Medieval Essex

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Henry VIII Testoon (shilling) from 1544-1547

Henry VIII Testoon (shilling) from 1544-1547

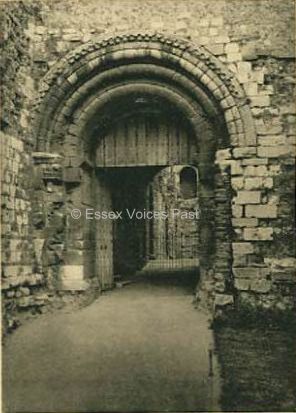

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20.

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20. Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘.

Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘. Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘.

Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘. And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

1538 (or 1539) In primo receyvyd of the lord of mysserowell & for the plowgh ffest – xls [40s] (folio 29r). This entry is ambiguous – did the Christmas Lord of Misrule also collect money for the plough-feast? Or have the churchwardens simply lumped the two events together in one entry? As the two events have not been recorded as separate sums of money, it is more likely the former.

1538 (or 1539) In primo receyvyd of the lord of mysserowell & for the plowgh ffest – xls [40s] (folio 29r). This entry is ambiguous – did the Christmas Lord of Misrule also collect money for the plough-feast? Or have the churchwardens simply lumped the two events together in one entry? As the two events have not been recorded as separate sums of money, it is more likely the former.

Sketch by Thomas Dugdale, c1848

Sketch by Thomas Dugdale, c1848 Postcard c1901-1910

Postcard c1901-1910 Postcard c1901-1910

Postcard c1901-1910

Postcard c1901-1910

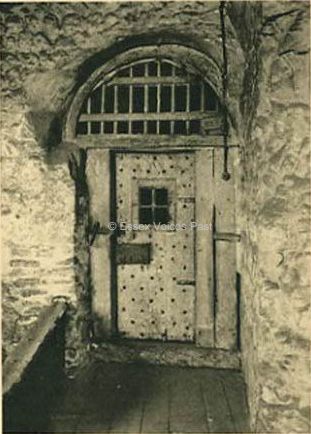

Postcard c1901-1910 Ground plan c1807

Ground plan c1807 Plan of the castle c1780

Plan of the castle c1780