You are cordially invited to attend my talk

Uncovering past secrets

Today’s post is about the contents of Tudor wills and how they can be used to inform the modern-day reader about religion during the turbulent reigns of Henry VIII and his three children. The text below formed one of the chapters within my dissertation Religion and Society in Great Dunmow, Essex, c.1520 to c.1560 from my Cambridge University’s Masters of Studies in Local and Regional history awarded to me in January 2012. The text here is in its entirety from my dissertation so reads more as an academic essay rather than a blog post. For this blog post, I have included headings (to break up the text) and images, my original was both heading-less and image-less. If you are wondering why my introduction and conclusion are so short, remember that this is just one chapter in a very lengthy 100 page dissertation and I had a very strict word count to adhere to. The dissertation’s overall introduction and conclusion was far more comprehensive. I have also had to re-arrange the two tables on this post from their original positions within my dissertations – so Table 2 now comes before Table 1. The research of wills I undertook for my dissertation is very different to my normal genealogical research. For genealogical research, I am normally sifting through the personal bequests so to find evidence of family relationships. But for my dissertation, I had to totally ignore family relationships and go for the ‘other bequests’.

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20.

St Mary the Virgin, the Parish church of Great Dunmow, circa 1910-20.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*- *-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Introduction

Historians have studied the wills of many English parishes to gain understanding about the impact of the Reformation. Eamon Duffy examined the wills of the Yorkshire village of Otley(1) and Caroline Litzenberger, in her analysis of the Reformation Gloucestershire, studied the wills of approximately 8,000 testators(2). Therefore, the analysis of wills is a significant methodology employed by historians to provide evidence for the acceptance (or non-acceptance) of religious changes during the Reformation.

Methodology

The methodology used for this article has been to locate, transcribe and analyse all wills for Great Dunmow for the period 1517 to 1565: 40 wills in total.(3) Litzenberger divided her Gloucestershire wills into elite and non-elite wills, but this division is not possible for Great Dunmow’s much smaller sample. Table 1 and Table 2 displays the results from this analysis and this article examines those results.

Great Dunmow’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy assessments listed 139 tax-payers and 1525-6 church steeple collection listed 165 donations. From these figures, it can be deduced many wills have not survived. Those that have are

The discovery of only two wills proved in the London Consistory Court is particularly disappointing. However, this has been caused because the registers from 1521 to 1539 are missing.(5) Moreover, the first surviving Great Dunmow will that was proved in this court, is from 1559. This demonstrates there are other inconsistencies within the surviving registers from the 1540s and 1550s with the wills for Great Dunmow almost totally missing. Great Dunmow was in the archdeaconry of Middlesex but many nearby towns and villages (for example, Maldon and Chelmsford) were in the archdeaconry of Essex. Any testator with land in only one archdeaconry had their will proved in that archdeacon’s court (and therefore, now their original wills are held by Essex Record Office). However, testators with land in more than one archdeaconry had theirs proved in the London Consistory Court (i.e. the official copies of their wills will be held by the London Metropolitan Archives in London). Therefore, many wills for the years 1520 to 1559 are missing for parishioners who were the ‘middling sort’ or elite (i.e. they owned land/property in both Great Dunmow and neighbouring villages or towns). The missing registers almost exactly span the offices of two incumbents of the bishopric of London: Cuthbert Tunstall, bishop 1522 to 1530(6) ; and John Stokesley, bishop 1530 to 1539(7). It could be speculated that the missing volumes were lost not long after these dates, perhaps handed over to the Elizabethan martyrologist, John Foxe, for his examination of early martyrs within the diocese of London.(8)

There is evidence within Great Dunmow’s Henrician churchwardens’ accounts which can also be used for will analysis. These accounts document six gifts of money from named parishioners to the church, but the wills from these people have not survived. However, as these donations were likely to have originated from wills, they have been included within this analysis. For example, vicar Robert Sturton’s missing will would undoubtedly contain a bequest to the church, as there is a 1528 churchwardens’ accounts entry ‘of[f] wylyem sturton of ye gyfte of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche…liijs iiijd [53s 4d]’(9). The churchwardens were diligent in recording bequests and gifts to the church in their accounts. This can be detected from John Skylton’s will of 1533 in which he left a bequest of 13s 4d to the church. This exact amount duly appeared in that year’s churchwardens’ accounts, given to the churchwardens by his wife.(10) Therefore, there is credibility to include gifts recorded within the churchwardens’ accounts within this analysis of wills.

Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘.

Above, Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (folio 9r) showing the gift from the former vicar. ‘Ite[m] Rec[ieved] of wylyem sturton of ye gyfe of M[aster] Sturton sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche liijs iiijd (53s 4d)‘.

Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘.

Will of John Skylton of Great Dunmow (January 1533), Essex Record Office D/ABW 8/28. The Tudor scribe who wrote the will (above) couldn’t write in straight lines! The request to the church starts on the third line… ‘hie awter [high altar – this is the end of Skylton’s tithe bequest] of the church – xxd [20d] also to the rep[er]ations [repairs] of the church of Du[n]mowe xiijs iiijd [13s 4d] also to the church of powles iiijd [4d – this is the bequest to St Paul’s cathedral in London]‘.

And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

And here’s the entry in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts showing that his widow had duly handed over the bequest to the church ‘Ite[m] Rc [Received] of Jone [Joan] Skylton of the gyfte of John Skylton – xiijs iiijd [13s 4d]’.

Analysis of Soul Bequests

[The table below for soul bequests was originally on an A3 sheet of paper. I have had to shrink it so that it fits this blog post. Click it to display it within a new window and then use your zoom facility to increase the size of the text. The wills for Elizabeth’s reign are only up until 1565 as this is the point my dissertation ended.]

Soul bequests within preambles of wills have been used by historians of Reformation England to ascertain religious changes. A Catholic preamble would include words similar to ‘almyghtie god & to our blyssed lady saynt mary the virgyn & to all the holy company of heaven’(11). An evangelical or Protestant might include words such as ‘Almighty God and his only Son our Lord Jesus Christ, by whose previous death and passion I hope only to be saved’(12). Somewhere in between would be other types of soul bequests. Litzenberger divided her wills into three major categories: ‘Traditional’ [i.e. Catholic], ‘Ambiguous’, and ‘Protestant’, and within these categories, wills were further sub-divided. Litzenberger’s categories have been used as a framework for the analysis of soul bequests for Great Dunmow’s wills; as demonstrated in Table 2. Categorising soul bequests have to be handled with caution. Wills were only ambiguous if there were no other bequests indicating that they were traditional. Some wills contain either a final stipulation to the executors to provide for the wealth/health of the testator’s soul, or the bequest for ‘tithes forgotten’. The existence of either clause, it can be argued, was the sign of a traditional will, as discussed below. Moreover, ambiguity might have been a defence employed by traditionalists against an increasingly hostile environment.(13) This strategy of ambiguity by traditionalists might account for the eight ambiguous Edwardian wills made during evangelical vicar Geoffrey Crisp’s time. Furthermore, a Protestant was unlikely to use an ambiguous soul bequest and would almost certainly proclaim their religion in unmistakable language.(14) Table 2 demonstrates there were no unquestionably Protestant soul bequests within the surviving wills of Great Dunmow.

Analysis of other bequests (not family)

There are other limitations when using wills for the analysis of religious belief. Duffy comments ‘wills tell us more about the external constraints on testators than they do about shifting private belief.’(15) External constraints could be the religious policy imposed by the monarch, for example, the Edwardian denouncement of purgatory, trentals and masses.(16) There were other constraints, including the scribe who wrote the will and the testator’s witnesses. Margaret Spufford, in her work on sixteenth and seventeenth century wills was the first historian to observe a will could be written by a scribe.(17) She stated

A man lying on his death bed must have been much in the hands of the scribe writing his will. He must have been asked specific questions about his temporal bequests, but unless he had strong religious convictions, the clause bequeathing the soul may well have reflected the opinion of the scribe or the formulary book the latter was using, rather than those of the testator. (18)

Some wills indisputably demonstrate the testator had not been influenced by a scribe or witness. Great Dunmow’s Marian will of Thomas Baker contains a traditional soul bequest along with bequests for tithes forgotten; and, even more revealingly, an obit and a solemnly sang dirge.

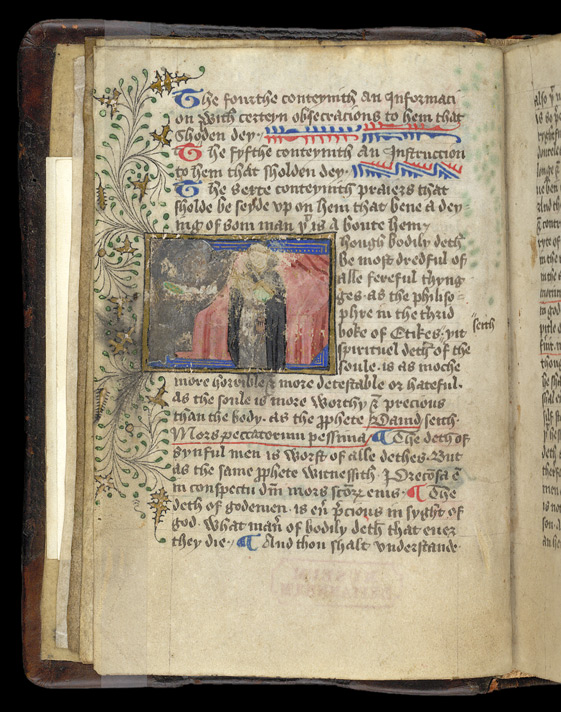

A priest providing Extreme Unction (the Last Rites) to a man in bed, from Pontifical; Tabula (England, 1st quarter of the 15th century), British Library’s shelfmark Lansdowne 451 f.234.

There is evidence of a Henrician scribe who was active in two 1520s wills from Great Dunmow, and he possibly used a book containing standard formulaic clauses. This type of precedent book was not unusual during the Tudor period.(19) The will of widow Clemens Bowyer, dated February 1526, almost exactly mimics the earlier will of John Wakrell (October 1525). Both wills have the same soul bequests (Catholic, as would be expected from this period); along with bequests to the high altar, to Saint John’s gild, to the church’ torches, and to the ‘moder holy chyrch of polye [St Paul’s] in London’. Both wills have a bequest for an ‘honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol & all crysten solls yn ye p[ar]rsche churche’. However this is crossed out in Bowyer’s will. It is possible the scribe copied the wording from his precedent book, and Bowyer made him cross it out. Trentals were a series of 30 Masses performed within one year, with three Masses on each of the ten major feast-days of Christ and Mary; the priest also had to perform other liturgical duties throughout the year.(20) This was a substantial undertaking, as demonstrated by Wakrell’s bequest of 10s for his trental. Maybe Bowyer did not have sufficient funds, and so made the scribe delete the bequest. This scribe was probably the parish priest, Sir William Wree who was witness to these and one other will. Also witness to Wakrell’s will was former vicar, Robert Sturton, described as ‘p[ar]rsche prest’. Sturton had resigned as vicar in 1523, so he was still performing some of his previous clerical duties.

Will of John Wakrell of Great Dunmow (October 1525), Essex Record Office D/ABW 39/7. The trental bequest reads (from the second word): ‘It[e]m I be q[u]esthe [bequeath] unto an honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol [soul] & all crysten [Christian] solls [souls] yn ye p[ar]iche chyrch \of D[u]nmowe a fore sayde xs [10s]’.

Will of John Wakrell of Great Dunmow (October 1525), Essex Record Office D/ABW 39/7. The trental bequest reads (from the second word): ‘It[e]m I be q[u]esthe [bequeath] unto an honest prest to synge a tryntall [trental] for my sol [soul] & all crysten [Christian] solls [souls] yn ye p[ar]iche chyrch \of D[u]nmowe a fore sayde xs [10s]’.

Will of Clemens Boywer [Bowyer] of Great Dunmow (February 1526), Essex Record Office D/ABW 3/8. The first crossing out is the trental: ‘It[e]m I bequethe to han [sic] honest prest to sy [n] ge [sing] a try[n]tall [trental] yn ye p[ar]rshe of myche [Much i.e. ‘Great’] D[u]nmow aforsad’. (Were pre-Reformation priests anything other than ‘honest’?)

Will of Clemens Boywer [Bowyer] of Great Dunmow (February 1526), Essex Record Office D/ABW 3/8. The first crossing out is the trental: ‘It[e]m I bequethe to han [sic] honest prest to sy [n] ge [sing] a try[n]tall [trental] yn ye p[ar]rshe of myche [Much i.e. ‘Great’] D[u]nmow aforsad’. (Were pre-Reformation priests anything other than ‘honest’?)

Old St Paul’s Cathedral – the ‘moder[mother] holy chyrch of polye [Paul] in London’ mentioned by 7 testators of Tudor Great Dunmow. St Paul’s was the mother church of the Diocese of London, and this diocese included the parish of Great Dunmow. The cathedral was the largest church in England and had the tallest spire in England. The spire was struck by lightning in 1561 and not replaced. St Paul’s was destroyed in 1666 – a casualty of the Great Fire of London. Sir Christopher Wren designed the new cathedral – one of the iconic images of today’s London.

Witnesses to Wills

The vicars and priests of the parish were witnesses to many wills. However, the decline in priests as witnesses demonstrates fewer priests were within the parish after Henry VIII’s break with Rome. Sir Edmund Clarke was witness to three traditional wills in the 1530s. Evangelical vicar Crisp, was witness to two Edwardian wills in 1551 and 1553; both with ambiguous soul bequests to ‘almighty god, my maker and redeemer’. Catholic vicar John Bird was witness to one traditional Marian will. The vicars must have witnessed many wills and surely influenced some testators by imposing their own beliefs on their dying parishioners. However, Elizabethan vicar, Richard Rogers, a former Protestant exile who spent Mary’s reign in Frankfurt,(21) did not enforce his beliefs on the wills of his parishioners. Seven Elizabethan wills were written during his tenure, although he was not witness to any of them. None of these wills were unequivocally and unmistakably Protestant: indeed the 1563 will of Gilbert Cooke had a traditional soul bequest including ‘the blesyd company of heavne’.

Priest administering last rites

from The Dunois Hours (Paris, c. 1440 – c. 1450 (after 1436))

British Library’s shelfmark Yates Thompson 3 f.211 .

The limitations of using wills to determine religious belief

Wills do not always accurately reflect the complete representation of a testator’s religious beliefs. In an investigation of late Medieval wills for All Saints, Bristol, the author of the study found the wills of some of the elite did not include bequests to the parish church.(22) However, the parish’s Church Books demonstrate that during these testators’s lifetime, substantial gifts, such as gilding of the Lady altar, and the refurbishment of the rood loft, had been made to the church. Furthermore, a wife often made donations after her husband’s death but during her lifetime, on behalf of them both. This generosity would most likely not have appeared in either the husband’s or his widow’s wills. This discrepancy between a testator’s will and the gifts made during their lifetime is also true within Great Dunmow. For example, Miles Docleye’s Edwardian will of 1551 has an ambiguous soul bequest and only bequests to his family; there are no religious bequests. It would appear his will was ambiguous but conforming to Edward’s Protestantism. However, Docleye, who must have been at least in his 50s when he died, had given money to each of the parish’s seven collections for traditional religious items during the 1520s and 1530s. It is impossible to determine if his beliefs had changed or if his will was conforming to Edwardian policy. It was probably the latter. This one example demonstrates that the analysis of wills for religious beliefs has its limitations. The laity of Great Dunmow had been investing in traditional religious artefacts throughout the 1520s and 1530s, but these donations are not apparent from their wills.

The importance of ‘tithes negligently forgotten’

The bequest to the high altar for ‘tithes negligently forgotten’ clause was an important part of pre-Reformation wills; and all ten Henrician wills have this bequest. One of the duties of the parish priest was to pronounce the Great Excommunication or General Sentence to his parishioners four times a year.(23) This proclaimed transgressions against the church; and debts (including unpaid tithes) were such transgressions. The bequest ensured the testator cleared his or her debt to the church and so their soul could benefit from prayers. Furthermore, unpaid debts meant the testator’s soul would be longer in purgatory, so this was an important bequest for traditional religion. Henry VIII banned the reading of the General Sentence in parish churches because it was vehemently against those who appropriated Church property or contested the authority of the Church(24), and, of course, Henry VIII had unquestionable contested the Pope’s authority in England.

This prohibition, along with the Edwardian theological retreat from the concept of purgatory,(25) was perhaps the reason why none of Great Dunmow’s Edwardian wills have the tithes to the high altar bequest. Moreover, the Great Dunmow’s high altar had been destroyed on the orders of Edward VI.(26) However, four Marian wills do have the clause; of these, three also have a traditional soul bequest. These four wills were written in 1557 and 1558; so it is possible this bequest was not included in earlier Marian wills because Great Dunmow’s high altar was still to be rebuilt after Catholic Mary came to the throne of England. In Elizabeth’s reign, Elizabeth Dygbey’s will written in December 1558 (i.e. one month after Mary’s death), also had a traditional soul bequest, along with the tithes clause. This was before the Marian high altar was taken down sometime between 1559 and 1561.(27) In 1564, John Byckner used a variation of the tithes bequest for a will which was otherwise ambiguous; the high altar had again been destroyed, so he left his money for ‘tithes forgotten’ to the ‘curate’. Byckner’s will is unusual because, apart from Dygbey’s will written shortly after Mary’s death, no other early Elizabethan will contains the tithes bequest. If this John Byckner, a wax chandler, was the same John Byckner, who lived in the High Street in 1525-6,(28) he would have been at least in his 60s and so perhaps had some of the old, traditional habits. This confirms the remark, ‘Wills were made usually by the old, who were generally less open to new ideas than the young or middle aged.’(29)

A priest excommunicating a group of people by raising a candle

from Omne Bonum (Ebrietas-Humanus) (London, England, c.1360-c.1375)

British Library’s shelfmark Royal 6 E VII f.75v.

Conclusion

The analysis within this articles has demonstrated that bequests within wills alone cannot substantially confirm the religious faith of a testator. However, it is clear that collectively the wills of Great Dunmow do demonstrate significant changes over time. Bequests to the church almost totally stopped after Henry VIII’s reign, in all probability because his attack on traditional religious artefacts made parishioners cautious. Not a single Edwardian testator made an unequivocally Protestant will, even with evangelical vicar Crisp present. Mary’s reign demonstrated a shift back towards traditional religion, with bequests to the high altar, and obits. The early years of Elizabeth’s reign demonstrate that wills had once again started to move away from traditional bequests. However, external factors could influence a testator’s will, for example, religious changes enforced by the monarch, local vicars, scribes and witnesses, and the age of the testator. Therefore wills cannot provide the complete account of the parishioners of Great Dunmow’s changing beliefs. Moreover, Henrician and Marian anti-Catholic events did take place in the parish with the 1546 re-enactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton, and Thomas Bowyer’s disobedience to the re-established Catholic Church. Therefore, wills can provide only a limited narrative regarding the changes experienced by this parish during the Reformation.

Details of a funeral

from Book of Hours, Use of Sarum

(England, S. E. (Suffolk, Bury St Edmunds?), 2nd or 3rd quarter of the 15th century)

British Library’s shelfmark Arundel 302 f.77v.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

Church End, Great Dunmow, postcard circa 1910-20.

Footnotes

(1) Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580 (2nd edn., 2005), pp.515-21.

(2) Caroline Litzenberger, The English Reformation and the Laity: Gloucestershire, 1540-1580 (Cambridge, 1997), pp.168-178.

(3) (n/a to this blog)

(4) This includes six monetary gifts, as documented in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, but a corresponding will has not survived.

(5) London Metropolitan Archives, Diocese of London Consistory Court Wills index (2011), (At the time of writing my dissertation, these indexes were in pdf file format and online at http://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk. However they do not appear to be there at present.)

(6) D. Newcombe, ‘Tunstal, Cuthbert’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition, May 2011), http://www.oxforddnb.com

(7) Andrew Chibi, ‘Stokesley, John’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online Edition, May 2011), http://www.oxforddnb.com

(8) Personal correspondence, Richard Rex, Cambridge, March 2011.

(9) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.7r.

(10) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fol.18v.

(11) Will of Katherine Smythe (1558), Essex Record Office, D/ABW/33/335.

(12) Margaret Spufford, ‘The Scribes of Villagers’ Wills in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and their influence’, Local Population Studies (1972), pp.28-43 at 29.

(13) Correspondence, Rex.

(14) Correspondence, Rex.

(15) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, p.508.

(16) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, p.505.

(17) Margaret Spufford, Scribes of Villagers’ Wills, pp.28-43.

(18) Margaret Spufford, Scribes of Villagers’ Wills, p30.

(19) Correspondence, Rex.

(20) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.370-371.

(21) Christina Hallowell Garrett, The Marian Exiles (Cambridge, 1966), p.273.

(22) Clive Burgess, ‘”By Quick and by Dead”: Wills and Pious Provision in Late Medieval Bristol’, The English Historical Review, 102 (October 1987), pp.837-858 at p.842.

(23) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.356-7.

(24) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.356-7.

(25) Eamon Duffy, Stripping the Altars, pp.504.

(26) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.40v.

(27) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.44v.

(28) Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, fo.2v.

(29) Robert Whiting, Local Responses to the English Reformation (Basingstoke, 1998), p.130.

(30) The first two columns of Table 2 have been taken from Caroline Litzenberger, The English Reformation and the Laity: Gloucestershire, 1540-1580 p.172

Notes

Great Dunmow’s original churchwarden accounts (1526-1621) are in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Please subscribe to my newsletter using the link below

I am planning exciting events during 2019 – including unique online courses:

My newsletter will give you more details about all my events, courses, talks and local history services.

You can also connect with me on Facebook and Twitter

Twitter: EssexVoicesPast

Facebook: Kate J Cole

| Post created 2013 and updated September 2019 © Kate J Cole | Essex Voices Past™ 2012-2019 |

A year ago today, I published my first post, Great Dunmow’s Medieval Manors, on this blog. Originally, I created my blog to publish some of my dissertation research ‘Religion and Society in Great Dunmow, Essex, c.1520 to c.1560′ from my Cambridge University’s Masters of Studies in Local and Regional history awarded to me in January 2012 (sadly, the degree no longer appears to be running).

However, over the year, this blog has evolved into a patchwork of posts all loosely based around the local history of the North Essex town of Great Dunmow, English medieval history, early-modern England and Tudor history. To celebrate my blog-anniversary, today and tomorrow I will be publishing my most viewed 12 posts from the last year. Thank you for reading my posts, writing lovely inspiring comments, and ‘talking’ to me on twitter. I look forward to writing another year of posts and sharing with you my view of England’s rich heritage and history.

Below are my most viewed top 6 posts from the last year.

1. Interpreting primary sources – the 6 ‘w’s – For all historians-in-training – analysing primary sources.

1. Interpreting primary sources – the 6 ‘w’s – For all historians-in-training – analysing primary sources.

2. Images of medieval cats – Cats, as illustrated on the folios of medieval illuminated manuscripts now in the care of the British Library.

2. Images of medieval cats – Cats, as illustrated on the folios of medieval illuminated manuscripts now in the care of the British Library.

3. Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow – The story of Queen Elizabeth’s I’s Royal Progress through Essex and Suffolk during the Summer of 1561.

3. Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Great Dunmow – The story of Queen Elizabeth’s I’s Royal Progress through Essex and Suffolk during the Summer of 1561.

4. The clergy in pre-Reformation England – The vicars and ‘Sirs’ of the pre-Reformation Catholic clergy with particular reference to the 1520s clergy to Great Dunmow.

4. The clergy in pre-Reformation England – The vicars and ‘Sirs’ of the pre-Reformation Catholic clergy with particular reference to the 1520s clergy to Great Dunmow.

5. Blacksheep Sunday: Witches, witchcraft and bewitchment – The tragic story of a neighbourly conflict in Great Dunmow during the 1560s which exploded into the accusations of witchcraft and bewitchment.

5. Blacksheep Sunday: Witches, witchcraft and bewitchment – The tragic story of a neighbourly conflict in Great Dunmow during the 1560s which exploded into the accusations of witchcraft and bewitchment.

6. Thomas Bowyer, weaver and martyr of Great Dunmow d.1556 – The story of how an established family from the town of Great Dunmow produced a son who in 1556 was burnt at the stake for his Protestant faith.

6. Thomas Bowyer, weaver and martyr of Great Dunmow d.1556 – The story of how an established family from the town of Great Dunmow produced a son who in 1556 was burnt at the stake for his Protestant faith.

Join me next time to discover my next top 12 posts (6-12)

Which were your favourite posts and why?

Please do leave your thoughts on my blog below.

Thank you!

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Today, 27th June, is the anniversary of the burning of thirteen people at Stratford le Bow in 1556, executed in the most horrible manner because of their religion and faith. It was the largest burning of a group of people in Tudor history, and this terrible spectacle was watched by a crowd of over 20,000 people.

Burning of 13 people (11 man and 2 woman) at Stratford le Bow June 1556,

Burning of 13 people (11 man and 2 woman) at Stratford le Bow June 1556,

from John Foxe, Acts and Monuments (1570 edition), p2135.

The story regarding this terrible burning in London is being retold today by myself on Spitalfields Life blog here. The story of one of those victims who perished in Queen Mary Tudor’s flames, Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow is retold here at Essex Voices Past.

Piecing together details about these men and women is difficult because, apart from John Foxe’s book, there is not much surviving contemporary evidence, particularly as these were not high-profile victims. However, during my research of Tudor Great Dunmow, I have been able to piece together circumstantial evidence regarding the background of Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow.

According to John Foxe’s 1563 version of The Acts and Monuments (more commonly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs),

Thomas bowyer sayde he was brought before one maister Wiseman of Felsed, and by him was sent to Colchester castel, and from thence was caryed to Boner Byshop of London, to be by him further examined.

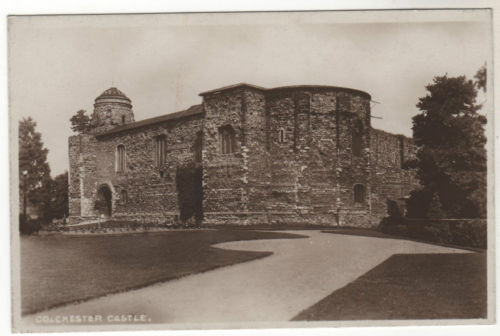

Colchester Castle – county gaol of Tudor Essex

Colchester Castle – county gaol of Tudor Essex

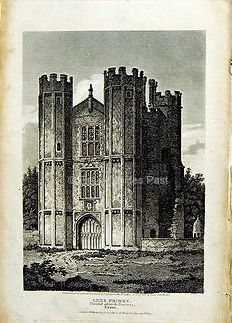

Felsted is the neighbouring village to Great Dunmow and Master Wiseman was probably the local JP whom Bowyer was hauled before. It is curious that Bowyer was not taken to the magistrates in Essex’s county town of Chelmsford. However, there is possibly a reason for this (or rather, a person): Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich. Lord Rich, that arch-villain of Tudor history, was an enthusiastic persecutor of Essex Protestant heretics during the Marian years. This enthusiasm was in spite of his earlier zealous support of Henry VIII’s break from Rome (resulting in his betrayal of Sir Thomas More), and his support of Edward VI’s Protestant religious changes. One of Rich’s many manors included his great mansion, Leighs Priory, (located a very short distance from Felsted) a former religious house granted to him by Henry VIII at its dissolution in 1536. Thus, Rich had very strong connections to Felsted and was buried in the parish church in 1567. With the presence of Lord Rich in Felsted, this must have been the reason why Bowyer was taken there, and not to magistrates in Chelmsford. Foxe did record that another victim who died alongside Bowyer, George Searle from White Notley (a village a couple of miles from Felsted), was taken before Rich. So the supposition that Richard Rich was involved in the case of Thomas Bowyer is entirely plausible.

Leighs Priory, Felsted (also known as Lees and Leez),

Leighs Priory, Felsted (also known as Lees and Leez),

home of Richard Rich, Lord Rich

That the small North Essex town of Great Dunmow had produced a weaver with such strong and unshakeable Protestant convictions is, on the surface, remarkable. However, the parish of Great Dunmow had already visibly demonstrated that many townsfolk supported Henry VIII’s break with Rome. This evidence is contained within an extraordinary folio of Great Dunmow’s beautifully tooled leather-bound churchwardens’ accounts, now in the care of Essex Record Office.

In the summer of 1546 (the final summer of Henry VIII’s life and reign), the townsfolk of Great Dunmow staged a remarkable anti-papist event involving the entire parish. It is very likely that an impressible 16 year old Thomas Bowyer was also present. This event took place during the parish’s annual Corpus Christi religious play when people from the neighbouring towns and villages came into Great Dunmow for the communal celebration of this Catholic religious feast-day. The churchwardens’ accounts itemise receipts for that year’s Corpus Christi play, followed by the money received from each named local village who attended the play (eleven villages in total).

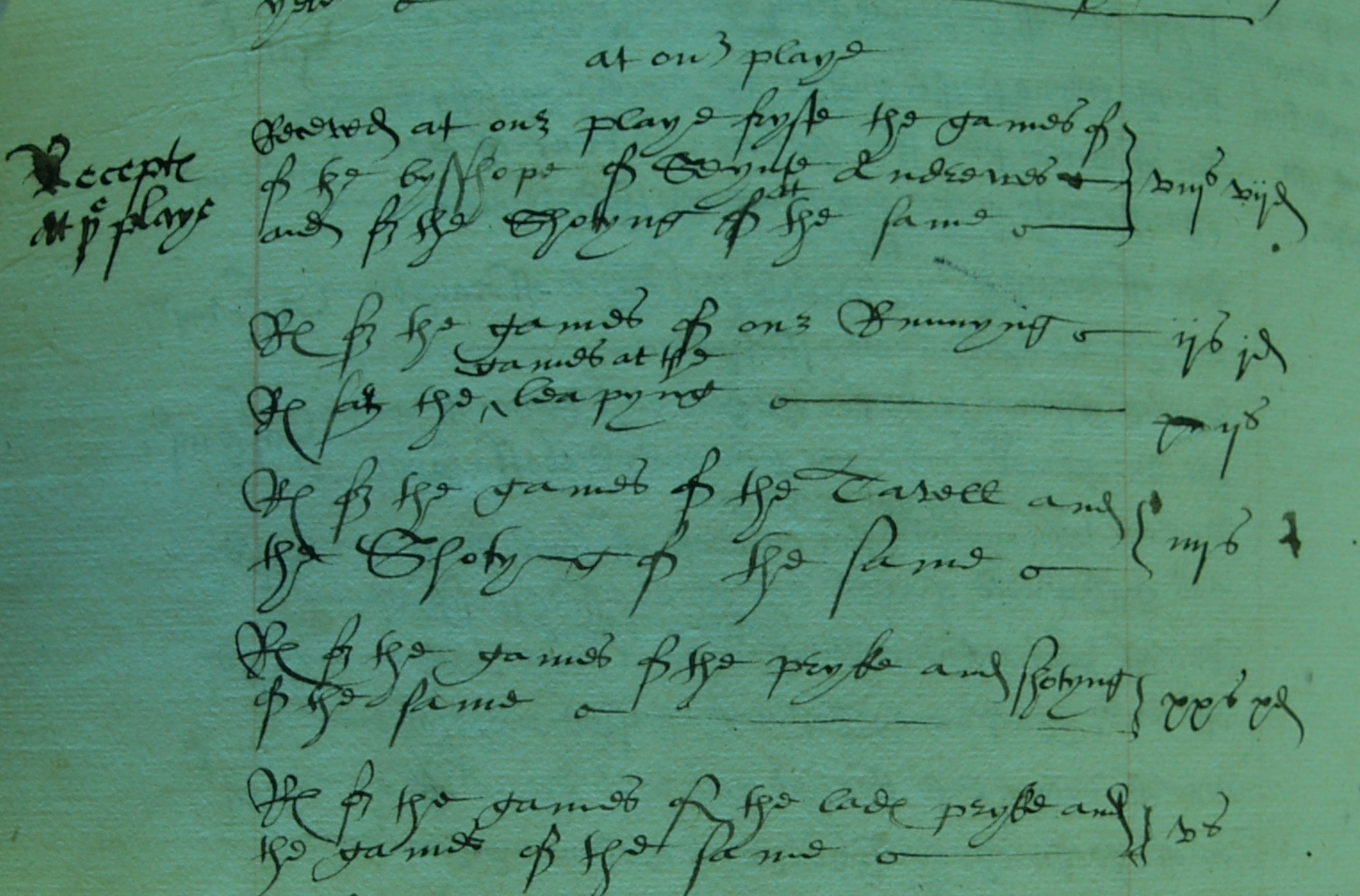

Entries for Great Dunmow’s June 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day

Entries for Great Dunmow’s June 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day

(Essex Record Office, D/P 11/5/1 f.39v)

[heading] At our playe

[in the margin] Recepte at ye playe

Receved at our play & fryste the games of of [sic] the bysshope

of saynte andrews and for the shottyng of at the same viijsvijd

Rec for the games of our runnyng ijsid

Rec for the \games at the/ leapyng ijs

Rec for the games of the casell and the shotyng of the same iiijs

Rec for the games of the pryke and shotyng of the same xxsxd

Rec for the games of the lade pryke and the games of the same vs

Deciphering this entry demonstrates that the people of Great Dunmow and surrounding villages had held an archery competition (the ‘shottyng’) which included shooting bows and arrows against an effigy of the Archbishop of Saint Andrews and at a structure which resembled the Archbishop’s Scottish castle (the ‘casell’). The ‘prykes’ were archery targets set at a specified number of paces away from the archer.

The reason for the staging of this remarkable event was because of a personal grudge of Great Dunmow’s evangelical vicar, Geoffrey Crispe MA, against Cardinal David Beaton. Beaton was the Catholic archbishop of Saint Andrews and the highest ranking cleric in a then Catholic Scotland. He had been murdered by Scottish Protestants in May 1546, three weeks previously to the feast-day of Corpus Christi, and his castle seiged. Beaton’s murder and the storming of his castle in Saint Andrews was in direct retaliation for him burning at the stake the Protestant Scottish martyr George Wishart a few months previously. Prior to his Protestant teachings in Scotland, George Wishart had been a lecturer at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge – the same college and university where Great Dunmow’s vicar, Geoffrey Crispe, had studied and had been a fellow. The vicar of Great Dunmow, Geoffrey Crispe, was a contemporary, friend and associate of Protestant George Wishart.

Three weeks after the murder of Cardinal Beaton and 450 miles away, Great Dunmow used that year’s Corpus Christi feast-day to reenact his murder and the storming of his castle. An event which must have been instigated and supported by Wishart’s friend and colleague, vicar Geoffrey Crispe. This very public celebration of the cardinal’s murder demonstrates that by 1546 there was very strong anti-Pope (and probably anti-Scottish) feeling within Great Dunmow. Moreover, as Beaton’s murder was welcomed by the English king, Henry VIII, the town was visibly demonstrating their loyalty to their monarch. This folio within Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts contain the only evidence for this event, so it cannot be determined if the motivation behind the celebrations was inspired by Crisp’s personal affiliations to Wishart, or the parish’s loyalty to their sovereign, or their changing religious theology. It was probably a combination of all three.

George Wishart (b. c1513, d. 1 March 1546)

Cardinal David Beaton,

archbishop of Saint Andrews

(b. c1494, d. 29 May 1546)

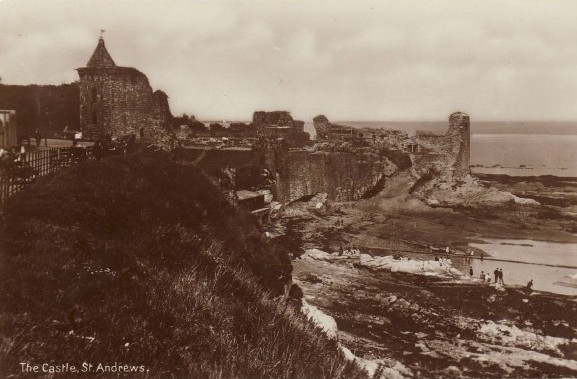

Ruins of Cardinal Beaton’s castle in St Andrews, Scotland.

St Andrews’ castle – laid siege by Scottish Protestants in retaliation for the burning of George Wishart. The English parish of Great Dunmow and its neighbouring villages re-enacted the storming of this castle three weeks later.

It is likely that an impressionable 16 year old Thomas Bowyer had been present at the reenactment of the shooting of Catholic Cardinal Beaton and the storming of his castle. Furthermore, it is also probable that he was one of those young lads who took part in the ‘games of the lade pryke and the games of the same’. These activities during Corpus Christi 1546 was a clear demonstration of the anti-papist feelings within the parish of Great Dunmow, and its surrounding villages. Moreover, vicar Geoffrey Crispe had embraced these religious changes to such an extent that at some point during his 1540 to 1554 tenure of the living of Great Dunmow, he had married and so had a wife. Many parishioners, led by vicar Crispe, had started to embrace Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the changing religious wind blowing through England. However, in June 1556, ten years after Great Dunmow’s anti-papist Corpus Christi feast-day, Thomas Bowyer was burnt at the stake in Stratford le Bow in punishment for being a Protestant. The winds of religious change (Catholic this time, led by the Pope in Rome), instigated by a Tudor English monarch, had once more blown through England and reached the north Essex parish of Great Dunmow.

The narrative about Great Dunmow’s reenactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton possibly explains why Thomas Bowyer had such strong Protestant convictions: he had probably learnt some of his faith through the parish’s anti-papist married vicar, Geoffrey Crispe. But who exactly was Thomas Bowyer of Great Dunmow, and how did he come to the attention of Bishop Bonner?

The Bowyer family of Great Dunmow occur within approximately ten legal documents, from 1483 to 1529, now held by Essex Record Office. The majority of these documents relate to land located near the parish church of St Mary the Virgin. Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts also contain numerous entries from the reign of Henry VIII for various Bowyers. These entries include a 1536-7 gift from ‘old Thomas Bowyer’ of 3s 4d (possibly a bequest from his, now lost, will) and entries for Mother Bowyer of Parsonage Downs, and Richard Bowyer of Church End. Parsonage Downs and Church End are two locations within Great Dunmow near the parish church. Richard Bowyer was a tenant of church land from at least the 1530s and paid yearly rent to the church, as recorded in churchwardens’ accounts. The final entry for the payment of his rent occurred in the early years of Edward VI’s reign: Richard Bowyer’s tenancy of church land must have been terminated at the time of the 1547-8 crown investigations into church lands. The Bowyer family are also documented within Henry VIII’s 1523-1524 Lay Subsidy returns for Great Dunmow: Clemens Bower (the ‘Mother’ Bower in the churchwardens’ accounts) had goods to the value of £6 and paid 3d in taxes, and Johanne (or, more likely, John) was assessed at 26s 8d and paid 4d.

The records prove that the Bowyer family of Great Dunmow were of the middling sort and were tenants of church land. No records exist to connect the martyr Thomas Bowyer to these Bowyers and he is not named in the churchwarden accounts. However, it is possible that the ‘Old Thomas Bowyer’ documented in the accounts was the martyr’s close relation (perhaps his father). Moreover, a few hundred yards away from Richard Bowyer’s tenement at Church End and just past the area still known to this day as Parsonage Downs where Mother Bowyer lived, is a bridge over the River Chelmer called ‘Bowyers Bridge’. This is said locally to be so named to commemorate the Protestant martyr, Thomas Bowyer. The date when the bridge became named is unknown. However, its close proximately to the land tenanted by the Bowyer family cannot be coincidence.

Bowyers Bridge, on the way to Little Easton c1901-1910

If the martyr, Thomas Bowyer, was related to Richard Bowyer, tenant of church property, and the Old Thomas Bowyer who left money in his will to the parish church, then he would have been well-known to the vicars of Great Dunmow. By the time of Thomas Bowyer’s martyrdom in 1556, anti-papist vicar Geoffrey Crispe had been deprived of the parish of Great Dunmow (because of his marriage). The next vicar of Great Dunmow was Catholic Doctor John Bird – the former Bishop of Chester – who had been deprived of his bishopric because he had married during Edward VI’s reign. Bird, having cast aside his wife, arrived in Great Dunmow in 1554, and became the suffragan bishop (i.e. assistant) to the Bishop of London, Edmund Bonner. The same Bonner, who was the zealous oppressor and burner of Protestants within his diocese which included the parish of Great Dunmow.

Furthermore, because of an unfortunate incident by the vicar, which took place in front of Bishop Bonner in the parish church of Great Dunmow in July 1555, Bird would have been anxious to show Bonner his Catholic allegiance. For this story, we once again turn to the Elizabethan martyrologist, John Foxe, who gave a heavily biased account of this incident in an unpublished manuscript (Harleian MS 42 f.1r-v). According to Foxe, Bird’s sermon that day in front of Bishop Bonner was about the text ‘Tu es Petrus, et super hanc petram aedificabo ecclesiam meam’ (‘Thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church’). Bird’s intention was to ‘prove the stability of St. Peter, and so successively of the Pope’s seat; but unfortunately wandered away into the account of St. Peter’s fall’ (W T Scott, Antiquities of an Essex Parish: Or Pages from the History of Great Dunmow (1873) p57). Bonner was infuriated by this anti-papist sermon and

stood upon thorns, for he made face, his elbows itched, and so hard was his cushion whereon he sat, that many times during the sermon he stood up looking towards the suffragane, giving signs (and such signs as almost had speaking) to proceed to the full event of the cause in hand. (Harleian MS 42 quoted in Scott, p57.)

The outcome of this disastrous sermon was that vicar Bird broke down to the great distress of the parish’s Catholics and the jubilation of the Protestants (Scott, p58). Vicar Bird must have been an old man in his 60s at this time, and had lived through so many religious changes. So the direction this sermon took was probably caused by the ramblings and forgetfulness of an old man. Therefore, despite Foxe’s insinuations, this sermon was probably not a deliberate attempt to displease Bishop Bonner or to show Protestant beliefs. However, the sermon had displeased Bishop Bonner and vicar Bird probably would have done anything to restore himself to Bonner’s favour.

It is therefore little wonder that Thomas Bowyer of Great Dunmow, whose family had been in the parish since at least the 1480s, came to the attention of the authorities. With Bishop Bonner’s loyal assistant, Dr John Bird, being the Catholic vicar of Great Dunmow, and Lord Rich living nearby in Felsted, Thomas Bowyer would not have been passed over by the anti-Protestant tide of persecution for long. Hence, on 27th June 1556, Thomas Bowyer, weaver of Great Dunmow was burnt at the stake at Stratford le Bow in London alongside 10 men and 2 women.

Modern-day plaque on Bowyers Bridge, on the main road from Great Dunmow to Thaxted by the turning for the village of Little Easton. The age of Thomas Bowyer on the plaque is incorrect: according to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Bowyer died aged 26.

Modern-day plaque on Bowyers Bridge, on the main road from Great Dunmow to Thaxted by the turning for the village of Little Easton. The age of Thomas Bowyer on the plaque is incorrect: according to John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Bowyer died aged 26.

Notes on the ‘bishop of Saint Andrews’ in the churchwardens’ accounts

Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts has been much examined by historians of the Reformation, Corpus Christi plays and early-modern drama in England. However, the entries on folio 39v for the ‘bysshope of saynte andrews’ and ‘casell’ have been either incorrectly transcribed or misinterpreted. In the secondary literature, ‘casell’ has been transcribed as either ‘tavell’ or ‘tarell’, and then totally ignored, and the reference to the ‘Bishop of Saint Andrews’ has been totally misunderstood. One historian even asserted that the entry to the bishop meant that Great Dunmow was acting the masquerade of a boy-bishop. All historians who have analysed the churchwardens’ accounts have totally missed the connection between the vicar of Great Dunmow to the Scottish Protestant martyr, George Wishart. This connection explains why such an extraordinary event took place in Great Dunmow in June 1546. In the secondary literature, I have found no other references to an English parish celebrating the murder of the Scottish Catholic archbishop. My post today is the first time this connection, and Great Dunmow’s reenactment of the murder of Cardinal Beaton during Corpus Christi feast-day 1546, has been made public. I discovered it in 2011 whilst researching for my Cambridge University master’s degree.

The historian’s craft of teasing evidence from sources

My main break-through came after I had told myself countless times that what I was reading HAD to make sense. The churchwarden accounts were the financial records of a parish church and therefore had to contain information about money either coming in or going out, along with the reason for the income/expenditure. Furthermore, the churchwardens’ accounts were an open record so could be read by any contemporary church or state official so had to make sense in that context. Indeed, Eamon Duffy has argued that it is likely many parishes’ churchwardens read their accounts out loud in front of their parish in a manner similar to a modern-day public meeting. Therefore, the language used in some churchwardens’ accounts imitates the behaviour of the spoken word (Eamon Duffy, Voices of Morebath, p23-4). So I read out-loud the entries about the bishop of Saint Andrews – and, once again, I heard our Tudor scribe’s Essex/Suffolk voice shining down through the centuries. However, I was somewhat startled when the scribe’s soft ‘casell’ came out of my mouth as a loud and clear ‘castle’! By reading the entry aloud, I had cracked the secret of this folio! After that breakthrough, and with a little more research into the men who were the Tudor vicars of Great Dunmow, everything else slotted into place.

The historical analysis techniques I used to decipher Great Dunmow’s 1546 Corpus Christi feast-day are discussed in the posts listed below.

– Interpreting primary sources – the 6 ‘w’s

– Primary sources – ‘Unwitting Testimony’

– Palaeography and reading between the lines

– The dialect of Tudor Essex

– Great Dunmow’s Tudor dialect

Parsonage Downs and Church End, home of the Bowyers of Great Dunmow

The pictures below are of Parsonage Downs (a small area of land located next to Bowyers Bridge) and Church End (a tiny hamlet next to the parish church). (Photos from 2012 and postcards from c1901-1910)

Parsonage Downs

Church End

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– The Tudor witches of Essex

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

– The craft of being a historian: Research Techniques

Luttrell Psalter, Psalm 79; Archers practicing at the butts

Luttrell Psalter, Psalm 79; Archers practicing at the butts

(East Anglia, England, 1325-35), shelfmark Add. 42130, f.147v, © British Library Board.

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Transcription of Tudor Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (1525-6)

| 1. Layde owte for ye cherche [Laid out for the church] |

|

| 2. In p[r]im[s] ffor iiij galuns oyle ffor ye lampe [In primis (Firstly,) for 4 gallons oil for the lamp] |

vijs iiijd |

| 3. Item for iij lampe glassys pryce [Item for 3 glasses for the lamp, price] |

iiid |

| 4. Item ffor mendying of ye ffurnes of ye lampe to scoryar [John Scoryar – documented as paying ‘nichell’ (nothing) to the church steeple collection. Item for mending of the furnace of the lamp] |

iid |

| 5. Item to John bykner for stykynge of ye Rood lyght [Item to John Bykner for striking of the Rood Light] |

xiiijd |

| 6. Item ffor strykynge of ye lyght before owre lady [Item for striking of the light before our lady] |

|

| 7. att ye hy alter & ye lyght on the basun \?li <illegible> off wax/ [at the High Altar & the light on the basin] |

vijd |

| 8. Item payde to Thom[a]s turner ffor mendynge off ye [Item paid to Thomas Turner for mending the] |

|

| 9. ledys in dyvers plasys & ffor ye longe ?? ye stepyll [leds in divers places and for the long ?? the steeple] |

vs viid |

| 10. Item ffor slenynge[??] of ?? new clothe [Item for sewing? of ? new cloth] |

vjd |

| 11. Item for p[ar]te of ye makynge of ye closett for ye Roode [Item for making part of the closet for the Rood]. |

iis |

| 12. Item to Marry\ou/ for mendying of ye bells on all hall[o]ws evyn [John Mayor – documented as paying 4d to the church steeple collection.] [Item to Mayor for mending the bells on All Hallows Eve(ning)] |

viijd |

| 13. Item payde to John oltyng for mendynge of [Item paid to John Oltyng for mending of] |

|

| 14. the clapers the yere’d ffore thatt we cam on [the (bell) clappers the years (be)fore that we came on] |

vis viijd |

| 15. Item for claperynge of iij letell bells for ye can[n]epe [Item for ?? of 3 little bells for the canopy] |

id |

| 16. Item to kynge for trussyng up of ye bell clapper [Item to King for trussing up the bell clapper] |

id |

| 17. Item to John Scoryar ffor mendynge of ye hutchys [Item to John Scorya for mending of the hutches] |

|

| 18. <illegible> and of ye stoles [and of the stools] |

vijd |

| 19. Item for hys borde ye ssame tyme [Item for his board (ie accommodation/lodgings) the same time] |

iiijd |

| 20. Item ffor ij planks ffor ye same hutchys [Item for 2 planks for the same hutches] |

vid |

| 21. Item to wyllem hott for nayles for yeene wark [Item to William Hot for nails for ?? work |

|

| 22. for ye same hutchys [for the same hutches] |

xd |

| 23. Item ffor oyl small nale for ye same [Item for oil??? small nail for the same] |

iid |

| 24. Item for ij dayes \warke/ off Thomas Savage ye same time [Item for 2 days work of Thomas Savage the same time – Thomas Savage donated the largest amount of money for the church steeple £3 6s 8d] |

viijd |

| 25. Item payde to burle in yernest off ye gyldynge off Awr lady [Item paid to burle? in earnest?? of the gilding of Our Lady. |

xxd |

| 26. Item for xxijth li of wex for ye Rood lyrite [Item for 22 pounds (li = libra) of wax for the Rood Light |

xijs xd |

| 27. Item to John Scoryar & Rychard hys brother [Item to John Scoryar and Richard his brother] |

|

| 28. ffor makynge off iij new stepys in ye vyce off the Rood loft [for making of 3 new steps in the vice of the Rood Loft] |

xd |

| 29. Item ffor xviij ryngs ffor ye nayle & the settyng on [Item for 18 rings for the nails & the setting on] |

iijd |

| 30. Item ffor a poly to hange ye basun on before owr lady of bedlem [Item for a pole to hang the basin on before Our Lady of Bedlem (Bethleham)] |

iijd |

| 31. Item ffor scorynge off ye grate & makynge off ye got?? ye cherch walk? [Item for scoring off the grate & making off the ?? the curch walk?] | ixd |

| 32. Item ffor a parcall lyne & ffor pyns & nalls ffor \ye/ sepolk[er] [Item for a parcel line & for pins & nails for the sepulchre |

iiijd |

| 33. Item ffor a New keye ffor ye stepyll dor [Item for a new key for the steeple door] |

iiijd |

| 34. Item payd ffor a blakk morres coatt | xiid |

| 35. Item payde ffor a sansbell rope [Item paid for a sansbell (sanctus bell) rope |

ijd |

Commentary

Yet another fascinating page from Great Dunmow’s history with so many interesting items. On this folio, all the items are all expenses i.e. items purchased by the churchwardens on behalf of Great Dunmow’s parish church, as they were ‘Layde owte for ye cherche’.

Great Dunmow’s Black Morris Coat

One of the most important items on this folio is the entry 2nd from bottom.

This can be transcribed as being a ‘Black Morris Coat’. At some points in my research, I did wonder if this entry was actually a ‘Black Mores Coat’. However, the entry very definitely shows a double ‘r’ and reading the accounts in their entirety many times over helped me hear the voice of the scribe and understand the dialect of Tudor Essex. The double ‘r’ was meant to be pronounced, and this entry was certainly for a ‘Mor-ris’ coat, not a ‘Mores’ coat.

This entry for Great Dunmow’s Morris Coat has been much cited by historians of medieval and early-modern English drama, Morris Dancing, the Catholic ritual year, as well as English folklore. If you have read any of the secondary literature on these topics and themes, then you will invariable find reference to Great Dunmow’s ‘Black Morris’ coat. And this is the primary source entry for it! However, this is the one and only documented reference to ‘Morris’ or ‘Black Morris’ in the entire hundred years of the surviving churchwardens’ accounts. There are no other mentions.

The entry is very short and concise, so by using ‘Unwitting Testimony’, it could be surmised that the coat was not an extraordinary purchase but its cost was significant. According to Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts, a man’s labour for one day cost 4d. Therefore, the purchase of this coat for 12d was a noteworthy sum of money. Moreover, the accounts were very precise that this was just one coat: ‘a blakk morres coat’ (in the singular). This coat must have been quite a spectacular item – full of finery and regalia. Today’s East Anglian modern revival of Molly Dancing is a thought to be a throw-back from English traditions performed at May Day and Plough Monday. Perhaps Great Dunmow’s early-modern Black Morris coat was a very early version of the magnificent robes that now adorn the modern-day Molly Dancers of East Anglia. On the previous folio of the churchwardens’ accounts (fol.4r), both May Day and the Plough-fest were itemised as bringing in revenue into the church. Therefore, it was more than likely that this magnificent Black Morris Coat costing 12d was worn at either (or both) festivities.

Below are photos my son took of the Molly Dancers on New Years Day 2012 at The Hythe, Maldon.

Other items of interest on this folio

Footnotes

1) Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England,1400-1580, (2nd Edition, 2005), p407.

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– Medieval Essex dialect

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Transcription of Tudor Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts (1525-6)

The top part of this folio has been transcribed here Collection for the church steeple (part 5).

| 23. S [decorative line separator] | |

| 24. Resayvyd of ye olde cherche wardens that is for | |

| 25. to saye wyllia[m] saud[e]r ro[b]art p[ar]car Raff melburne & \Thomas/ harvy | xiiijs |

| 26. Item Resayvyd att ye plowfest in ye towne | viijs jd |

| 27. Item off Nycolas P[ar]car of dansynge mony | iiijs iiijd |

| 28. Item off Wylyem swetyng of ye gyft of olde hall | ijs viiid |

| 29. Ite off may money the hole su[m] | xxviijs iiijd |

| 30. Ite att Corpus Xrsti ffeste | xxiijs |

| 31. Item off John pole \for a yerys farme & for a ??? | vjs viijd |

| 32. Rentt | |

| 33. Resayvyd the cherche rentt ffor ye hole yere ye sum | xxxiiijs ijd |

| 34. Ite off steworde for ye brykke ych [which] was left | xvid |

| 35. Ite off John atkynso[n] for a fewe bryks & a letell | |

| 36. wete lyme & a tabbe ych [which] thay carryd watt in ye sum | ixd |

| 37. Ite off ye glon?? ffor a ladder pryce | iiid |

| 38. Ite ffor a rope sold to ye good ma[n] fyche pryce | xijd |

| 39. Ite resayvyd ffor \ye/ scaffold off Thom[a]s Savage | iijs iiijd |

| – | |

| 40. Sum xviij li xs vd [£18 10s 5d) | |

| 41. Sum ??th rec[eived] ?? Anni xxli ijs jd |

Commentary

There are many interesting pages within the churchwardens’ account-book and this page has to rank high up the list of intriguing pages – not for what it says, but more what it doesn’t say!

The entries on this page are directly after the parish collection for the church steeple so cover the period 1525-6. Therefore, they are the first receipts for money received by Great Dunmow’s church recorded in the leather account-book. Churchwarden accounts or church records for Great Dunmow prior to 1525-6 have not survived. However, several entries on this folio indicate that the previous churchwardens had also kept careful accounts prior to 1525-6.

Churchwardens – Line 24/25:

fo.2r recorded that the current (ie 1525-6) churchwardens were Thomas Savage, John Skylton, John Nyghtyngale and John Clerke. This folio records that before them, the previous churchwardens were William Saud[e]r (probably ‘Saunder(s)’ – the churchwardens’ scribe had a soft Suffolk-like accent and didn’t pronounce hard ‘n’s , see The dialect of Tudor Essex), Robert Parker, Raff/Ralph Melbourne, and Thomas Hervy (Harvey?). As Medieval and Tudor churchwardens were often in office for two years, it is likely that these men were churchwardens for the periods 1523-4 and 1524-5. The 14 shillings which the old churchwardens handed over to the 1525-6 set was either their cash-in-hand money left over from their tenure or their own money to make up shortfall in the accounts (or a mixture of both). Medieval and Tudor churchwardens were personally liable for any shortfall in their church’s finances at the end of their period in office. It is because of this personal liability that the accounts of Medieval and Tudor churches were so meticulously documented and recorded.

Plough Monday – Line 26:

The plough-feast was celebrated on the first Monday after the Epiphany (Twelfth Day) in January and was the traditional start to the new agricultural year. The young men of the town dragged a plough from door to door in the parish collecting money. If people did not hand-over money, then a ‘trick’ would have been played on the unlucky house-holder (an event similar to today’s Halloween Trick or Treating). This ‘trick’ was likely to have involved the young men ploughing a furrow across the offender’s land. Money received from Great Dunmow’s plough-feast activities was recorded throughout the Henrician churchwarden accounts. It was likely that this was already a well-established money-making activity for the church within Great Dunmow before this first recording of the event within the leather account-book in 1526. This can be determined by the brevity of this entry which could be interpreted that the churchwardens did not need a full and complete explanation about this particular activity. This was the yearly Plough-Feast – so therefore everyone knew what happened – all that needed to be accounted for was the money received! The churchwardens’ accounts do not record what happened to the money raised from Plough Monday. However, it is likely that the money was used to maintain a ‘plough light’ (candle) within the church. The plough light was one of the many ‘lights’ banned and extinguished by Henry VIII in 1538.

The Wikipedia Plough Monday entry suggests that the Plough Monday customs were revived in the 20th century in the East of England and are associated with Molly Dancers. Below are photographs my son took of the Molly Dancers on New Year’s Day 2012 at The Hythe, Maldon. He’s only aged 8 so the photos are a bit blurry! All photos are copyright of The Narrator, 2012.

Dancing money – Line 27:

Unknown what this ‘dancing money’ was for. Nicholas Parker was one of many Parkers in Great Dunmow but there was only one Parker with the Christian name of Nicholas. In the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy, Nicholas Parker was assessed as having goods to the value of 23s 4d. In the parish collection for the church steeple, he was recorded as living in Bullock Row and paid 8d towards the collection for the church steeple (fo.2v–fo.3r). It was likely that Nicholas Parker collected money on behalf of Great Dunmow’s parish church for ‘dancing’ and gave that money to the churchwardens. The churchwardens were scrupulously thorough in recording which of the many Catholic feast-days money was collected in for the church. Thus, there are receipts for ‘the plough-feast’, ‘Corpus Christi’ and ‘May Day’ on the same page as this entry. As the entry does not specify a precise feast-day or event, it is possible that this was money collected at some type of ‘general’ dance which was associated with the parish church but not connected with any feast-days within the regular Catholic ritual-year.

Old Hall – Line 28:

Unknown what the ‘old hall’ was. It is possible that this was a bequest in the will of a William Sweeting. Unfortunately not many Great Dunmow wills from this period have survived and there is no trace of William Sweeting’s will from this date, so it cannot be established if this was a bequest. (A later blog will explain the reason why there are so few surviving wills in Great Dunmow.) The only William Sweeting to be assessed in the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy had goods to the value of 40s (so was of moderate wealth). However, it is possible that this 1525-6 entry was a gift, rather than a bequest because a William Sweeting is documented regularly in parish collections after this date in the churchwardens’ accounts.

– 1525-6 church steeple collection: William Sweeting lived in Bishopswood and contributed 6d.

– 1527-9 church bell collection: William Sweeting lived in Bishopswood and contributed 5d.

– 1529-30 church organ collection: William Sweeting contributed 2d (dwelling-places not recorded).

– 1532-3 new gild collection: William Sweeting contributed 2d (dwelling-places not recorded).

– 1537-8 great latten candlestick collection: William Sweeting contributed 1d (dwelling-places not recorded).

A William Sweeting, ‘the elder’, was the witness to the 1552 will of Robert Grene(1).

May day – Line 29:

May money 28s 4d. This money received for ‘activities’ held on May-day is a significant amount of money. Records in Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts show that an average daily wage for a labourer was 4d – thus the money raised for May-day equalled approximately 85 days from a labourer. This was a much larger event than the yearly Plough-Feast and received more money. From these scant pieces of evidence, it can be interpreted that the May-day money was collected from possibly the entire parish of Great Dunmow (and probably also other nearby towns and villages – as discussed in later blogs). Again, the shortness of the entry demonstrates that receiving money from May-day was a well-established practice in Great Dunmow by the time of its first entry in the new leather account book of 1526.

This entry does not explain what happened in Great Dunmow on May Day. Wikipedia suggests some of the activities that might have taken place at May Day.

Corpus Christi – Line 30:

Corpus Christi feast 23s. The shortness of this entry is both intriguing and annoying in equal measures! Once again, this was a substantial amount of money, and the briefness of the entry implies that Corpus Christi was a well established feast within Tudor Great Dunmow. Regular Corpus Christi entries are documented throughout the rest of the Henrician Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts. These other entries are much more detailed and thorough, allowing the modern-day reader the most amazing insight into the world of Tudor Great Dunmow and the hierarchical relationship between this small parish and their neighbouring towns and villages. Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi feast, as documented in the churchwarden accounts, has been greatly studied throughout secondary literature on medieval English drama and late medieval religious practices. My own Cambridge University’s master’s dissertation spent over half of the word count discussing and analysing what actually happened during Tudor Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi feast-day. My own account provides an alternative narrative to the explanation provided by other historians (most of whom do not appear to have consulted directly with the original churchwarden accounts nor have walked the streets of the town). As this was such a critical part of my masters’ dissertation, my interpretation of Great Dunmow’s Corpus Christi plays will be discussed in detail in a later blog.

Detail of a miniature of a bishop carrying a monstrance in a

Corpus Christi procession under an canopy carried by four clerics

The Lovell Lectionary. Harley 7026, f13 (England, c1400-c1410),

© British Library Board

Rent of church land – Line 33:

Total rent received in for various church lands. In later years, church rent is fully itemised along with the name of each tenant.

Building materials – Line 34-39:

This part of the accounts is still the receipts (money in) for the period 1525-6. These entries demonstrate that the church (and the churchwardens) were selling items of building materials to some of the townsfolk of Great Dunmow. John Atkinson bought a few bricks and a small amount of wet lime. Mr Fyche (Fitch?) bought some rope, and Thomas Savage bought some scaffolding. This last item by Thomas Savage is interesting for several reasons: firstly Thomas Savage was the man who made the largest contribution towards the church steeple and was ultimately awarded the contract for building the steeple (Henry VIII’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy Tax). Secondly, this entry demonstrates that there were items of scaffolding within the parish church in 1525-6. Either this scaffolding was in the church in the years prior to the building steeple or its existence was because of the construction of the new church steeple. The Victorian vicar of Great Dunmow, W. T. Scott, in his 1873 history of Great Dunmow narrated that there was extensive building work in the church in the years before the church steeple was rebuilt in 1525-6.(2) So there were plenty of reasons for scaffolding to be within the church.

The significance of Thomas Savage’s scaffolding will be discussed in a later blog post.

Footnotes and Further reading

1) Will of Robert Grene, husbandman (March 1552), Essex Record Office, D/ABW 16/83.

2) Scott. W.T., Antiquities of an Essex Parish: Or pages from the history of Great Dunmow (London, 1873) p.20.

For further information on the Catholic religious ritual-year in late medieval/Tudor England, see

– Hutton, R., The rise and fall of Merry England: The Ritual Year 1400-1700 (Oxford, 1994).

For further information on the Plough-feast, see the following websites

– http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plough_Monday

– http://www.ploughmonday.co.uk/

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– Medieval Plough Monday

– Pre-Reformation Catholic Ritual Year

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Family members mentioned in the churchwarden accounts include:

– Robert Sturton, vicar of Great Dunmow 1492-1523

– Robert Sturton, church clerk of Great Dunmow

– Robert Sturton

– William Sturton

– Stephen Sturton

– Alexander Sturton

Robert Sturton – vicar of Great Dunmow 1492-1523

Patron for the living of Great Dunmow: Dean and Fellows of Stoke College, Clare, Suffolk.

Reason for leaving the living of St Mary the Virgin, Great Dunmow, 1523: Resigned

University/degree: Described as ‘master’ in the churchwarden accounts indicating he was an M.A. (Master of Arts). Unknown which university.

1514: possibly the same Robert Stourton (described as a ‘Professor of Theology’ i.e. S.T.P.) who was rector of Long Melford, Suffolk.(1) Long Melford is 28 miles away from Great Dunmow.

19 April 1510: Robert Stourton, clerk, of Great Dunmow, pardoned by Henry VIII.(2)

Died by 1529. The churchwardens’ accounts detail of 53s 4d, a gift from Robert Sturton ‘sumtyme vycar of thys chyrche’. The money was given to the churchwardens by William Sturton.(3) It can be assumed William and Robert were related.

Notes on the Sturton family of Great Dunmow

There were many Sturtons within Tudor Great Dunmow. William Sturton was assessed in the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy for goods to the value of £40.(4) Two Robert Sturtons were also assessed, both with goods to the value of 20s. Stephen Sturton was also assessed. As the clergy were exempt from the Lay Subsidy, this implies that, including the vicar, there were three Robert Sturtons in Great Dunmow. Robert Sturton, the church clerk from the start of the churchwardens’ accounts until the mid-1540s was one of them. Throughout the Henrician churchwardens’ accounts, his wife received payment from the churchwardens for washing the church’s linen.

The only Sturton will to have survived is Alexander Sturton’s will of 1553. Alexander Sturton, of Clopton Hall, bequeathed money to the children of Stephen Sturton, Thomas Sturton, Robert Sturton and William Sturton (all deceased).(5) This suggests that Alexander Sturton was possibly the son of one of the three Robert Sturtons. Clopton Hall was one of Great Dunmow’s medieval manors.

Two William Sturtons from Great Dunmow were educated at Cambridge University. In 1526 William Sturton, aged 18, a scholar from Eton, of Dunmow, Essex, matriculated at Kings. He became a fellow of Kings College 1529-30, ordained Deacon of Lincoln 1530, and Precentor of Kings College 1541-9.(6) The other William Sturton of Great Dunmow matriculated at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge in 1564 aged 16 and was the son of Alexander Sturton.(7)

Thus, there is both circumstantial and solid evidence linking these Sturtons together. The evidence demonstrates they were an elite and well-established family. It is likely they were related to the Lord Stourtons of Stourton, Wiltshire.

In the early fifteenth century, Sir John Moigne held the Manor of Great Easton along with the advowson of the village’s church. Sir John’s heirs were his daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, Sir William Stourton. Sir William was presented to the rectory of Great Easton on the 3rd January 1408. Sir William’s Inquisition Post Mortem took place in Great Dunmow in the regnal year I Henry V. (1413-4). His son, John Stourton (who later became 1st Lord Stourton), was presented to Great Easton’s rectory on 5th January 1427. Throughout the fifteenth century and early sixteenth century, the House of Stourton held the Manor of Great Easton, and also the Manor of Blamster in the same village. Great Easton remained part of the Stourton estate until William, 7th Lord Stourton, sold the Manor and advowson in 1536.(8) Great Easton is a village 2.5 miles from Great Dunmow.

Great Easton, Essex, 2012

Great Easton, Essex, 2012

© Essex Voices Past 2012.

Henry VIII’s Pardon Rolls of 1509-14 documented William Stourton, knight, Lord Stourton, as the tenant of the manor of Estaynes ad Montem, Essex [Great Easton].(9) It has been suggested the true phonetic spelling of the name ‘Stourton’ is ‘Sturton’.(10) The scribes who wrote the churchwardens’ accounts used phonetic spellings for many names and places.

Therefore, it is probable Robert Sturton, vicar of Great Dunmow, and the other Sturtons of Great Dunmow, were distant relations to the House of Stourton.

Footnotes:

1) William Parker, The History of Long Melford (1873), 35.

2) J.S. Brewer (ed.), ‘Henry VIII: Pardon Roll, Part 1’ in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1: 1509-1514 (1920), 203-216, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=102632 .

3) Great Dunmow, Churchwarden accounts (1526-1621), Essex Record Office D/P 11/5/1, fo.7r.

4) Hundred of Dunmow: Calendar of Lay Subsidy Rolls (1523-4), E.R.O., T/A427/1/1.

5) Will of Alexander Sturton (1553), E.R.O., D/ABW 33/226.

6) John Venn, ‘William Sturton’ in Alumni Cantabrigienses Part I Volume IV (Cambridge, 1927), 181.

7) Venn, ‘William Stoorton’. in Alumni Cantabrigienses Part I Volume IV, 181.

8 ) Lord Mowbray, Segrave, and Stourton, The history of the noble house of Stourton (1899), 105-7 and 151.

9) J.S. Brewer (ed.), ‘Henry VIII: Pardon Roll, Part 3’ in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 1: 1509-1514 (1920), 234-256, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=102634 .

10) Mowbray, Stourton, 2.

Postcards displayed on this page in the personal collection of The Narrator.

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Pre-Reformation English church clergy

– Great Dunmow’s Medieval manors

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Within the 1525-6 collection for Great Dunmow’s church steeple, two vicars and two parish priests are recorded at the start of the list. The two priests can be detected from the suffix ‘Sur’ [Sir] alongside their names. ‘Sir’ was a courtesy title given to medieval parish priests and should not be confused with the title ‘Sir’ as given to knights. This use of ‘Sir’ for the parish priest was widespread throughout pre-Reformation England and only died out during the Elizabethan era with the end of Catholicism as the recognised church within England. Thus, the Tudor parish priest of Eamon Duffy’s The Voices of Morebath was ‘Sir’ Christopher Trychay (pronounced ‘Tricky’).

According to the 1525-6 returns for the church steeple, the two parish priests in Great Dunmow were

– Sur John mylton

– Sur Wyllyem Wree