Bosworth Field: 22 August 1485

If you watched the recent BBC drama, The White Queen, and its bloody climax – the Battle of Bosworth Field – you would be forgiven for thinking that the battle took place during late autumn or even during early winter. For, according to the Beeb, a thick covering of fallen leaves lay on the battlefield floor and light snow covered the bridleways.

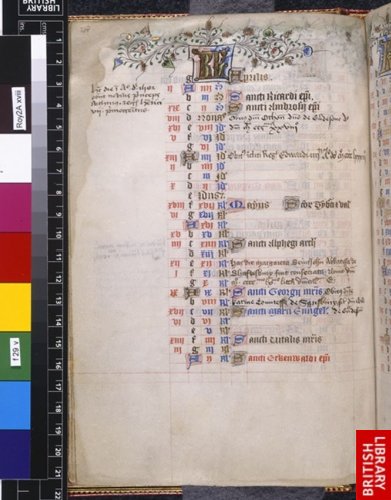

But the battle didn’t take place during winter. It took place during the high summer of 1485 – on Monday, 22nd August, to be precise. On the 7th August, Henry Tudor, soon to be crowned on a battlefield as King Henry VII, landed off the Welsh coast at Milford Haven. By late August, he was seven miles west of Leicester, near the village (or, in those days, the hamlet) of Market Bosworth. Margaret Beaufort (born 1443, died 1509), the mother of Henry VII, recorded these momentous events in her Book of Hours.

‘August’ from The Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours (England, S. E. (London), c. 1430,

‘August’ from The Beaufort/Beauchamp Hours (England, S. E. (London), c. 1430,

before 1443) shelfmark Royal 2 A XVIII f. 31v. (We do not know if this is her hand or if a scribe wrote the entries for her.)

The first left margin note in black reads

The day landed king harry the vijth at milford have[n] the yere of o[u]r lord vijth cccc lxxxv [1485]

The second left margin note reads

The day king harri the vijth won[n] the feeld [field] wher was slayn ki[n]g Richard the third Ao Do[m] 1485

The day before the battle, on the 21st August, King Richard III, along with an army of 12,000, rode out from his temporary accommodation at the White Boar Inn in the city of Leicester and set up his overnight camp in a field on Ambion Hill.

Early 20th Century etching of the Blue Boar Inn, Leicester. King Richard III spent the night of the 20th August 1485 in the Inn. It is alleged that he left his bed behind in the inn – perhaps he thought that he’d be coming back to the inn after he had dispatched his enemy, Henry Tudor. A white boar was the personal emblem of Richard III. Legend has it that the inn was originally called the ‘White Boar’ but after the battle and the death of Richard, the inn-keeper hastily changed the inn’s name to the Blue Boar.

Early 20th Century etching of the Blue Boar Inn, Leicester. King Richard III spent the night of the 20th August 1485 in the Inn. It is alleged that he left his bed behind in the inn – perhaps he thought that he’d be coming back to the inn after he had dispatched his enemy, Henry Tudor. A white boar was the personal emblem of Richard III. Legend has it that the inn was originally called the ‘White Boar’ but after the battle and the death of Richard, the inn-keeper hastily changed the inn’s name to the Blue Boar.

By the end of that fateful day, 22nd August 1485, King Richard III, the last of the Plantagenets, lay dead on the battlefield. And the Tudor dynasty began with King Henry VII crowned on Crown Hill in the nearby village of Stoke Golding by the treacherous Lord Thomas Stanley, the new king’s step-father.

King Richard III holds a council of war before the battle.

King Richard III holds a council of war before the battle.

King Richard III’s trusty advisers.

King Richard III’s trusty advisers.

The general area of the Battle of Bosworth Field. These photos were taken in the early summer of 2013. In August 1485, it is likely that these fields had the remains of that year’s crops still in the ground.

The general area of the Battle of Bosworth Field. These photos were taken in the early summer of 2013. In August 1485, it is likely that these fields had the remains of that year’s crops still in the ground.

The general area of the battle. By the end of the battle, it is thought that approximately 1,000 men on Richard’s side lay dead on the field, along with 100 men from Henry Tudor’s forces.

The general area of the battle. By the end of the battle, it is thought that approximately 1,000 men on Richard’s side lay dead on the field, along with 100 men from Henry Tudor’s forces.

Overlooking the general area of the battle-site. The spire in the distance is the (post-medieval) church spire of Stoke Golding, near to which the first Tudor King of England was crowned.

Overlooking the general area of the battle-site. The spire in the distance is the (post-medieval) church spire of Stoke Golding, near to which the first Tudor King of England was crowned.

1813 Monument to Richard III. During the battle, the King drunk from the well that was located here.

1813 Monument to Richard III. During the battle, the King drunk from the well that was located here.

The Fellowship of the White Boar’s plaque.

The Fellowship of the White Boar’s plaque.

Legend has it that the dead king’s body was brought back to Leicester that same evening. Stripped naked and devoid of any dignity or kingly regalia, his body was put on display for several days in Leicester. His enemies (and, of course, his followers) could see for themselves that he really was dead and their new king was Henry VII. Shortly afterwards, he was buried quietly, without ceremony, in the church of the Greyfriars – a Franciscan monastic order.

Modern-day statue of Richard III in a park in Leicester.

Modern-day statue of Richard III in a park in Leicester.

Of course, over 520 years later, we now know this legend to be true. King Richard III was indeed buried by the Franciscans in their monastery, where he lay undisturbed until his discovery in 2012. I, like many other people around the world, was riveted to the television during the live press release by Leicester University in February 2013, when they confirmed to the waiting world that the body that they had found was indeed that of the last of the Plantagenets. As the Tudor kings of England had so rightly said, Richard III really did lyth buryed in Leicester.

Richard ye was sonne to Richard Duwke of yorke & brother un to kyng Edward ye iiijth Was kyng after hys brother & raynyd ij yeres & lyth buryed at leator [Leicester]. From Biblical and genealogical chronicle from Adam and Eve to Edward VI (England, S. E. (London or Westminster), c. 1511 with additions before 1553) shelfmark King’s 395 ff.32v-33

Richard ye was sonne to Richard Duwke of yorke & brother un to kyng Edward ye iiijth Was kyng after hys brother & raynyd ij yeres & lyth buryed at leator [Leicester]. From Biblical and genealogical chronicle from Adam and Eve to Edward VI (England, S. E. (London or Westminster), c. 1511 with additions before 1553) shelfmark King’s 395 ff.32v-33

Watching the astonishing live press release – showing the perfect synergy of archaeology, genealogy, forensic science, and DNA science – was my small home educated son. He was entranced by the news. So, keen to capture his excitement, a few months later we headed north to Leicester for our most spine tingling School Trip Friday for academically challenged.

If Leicester’s one-way system had been in existence in 1485, then Richard III would never have made it out of the city and into the nearby villages and fields to meet his nemesis. In the 21st Century, guided by my trusty SatNav (who told me several times to ‘please take the 7th exit’ as I repeatedly circled the city), I eventually managed to navigate my way into Leicester, ready for a weekend of finding Richard. Trying to be as authentic as possible, I decided to stay in the exact location where Richard III had spent his second-to-last night on earth – the Blue Boar Inn. Except, of course, the Blue Boar Inn has long been demolished and swept away, but in its place is another hostelry with ‘blue’ as its insignia. Yes, my son and I stayed in the Travelodge – a modern 21st Century inn built on the exact site of its predecessor, the Blue Boar Inn.

The Blue Boar Inn 2013 (aka Travelodge). The area is continuing its medieval drunken past by being, in the 21st century, the weekend home of countless hen and stag parties. The location is now part of Leicester’s multi-lane one way system, and so my son and I spent two nights sleeping more-or-less on a massive roundabout, with the steady stream of all-night cars noisely whizzing around the city.

The Blue Boar Inn 2013 (aka Travelodge). The area is continuing its medieval drunken past by being, in the 21st century, the weekend home of countless hen and stag parties. The location is now part of Leicester’s multi-lane one way system, and so my son and I spent two nights sleeping more-or-less on a massive roundabout, with the steady stream of all-night cars noisely whizzing around the city.

As well as visiting the site of the Battle of Bosworth (and the wonderful Bosworth Battlefield Heritage Centre), we, of course, made our way into the centre of the city to find Richard at the temporary exhibition within the medieval guildhall.

My son comes face to face with a medieval king.

My son comes face to face with a medieval king.

The spire of Leicester Cathedral, overlooking the medieval guildhall.

The spire of Leicester Cathedral, overlooking the medieval guildhall.

Leicester Cathedral and the Guildhall.

Leicester Cathedral and the Guildhall.

Looking in one direction: the precinct of the Cathedral. To take this photograph, I had to stand directly in the middle of the small road shown in the next photograph.

Looking in one direction: the precinct of the Cathedral. To take this photograph, I had to stand directly in the middle of the small road shown in the next photograph.

Looking in the opposite direction: the location of the Greyfriars monastery. Behind the building on the left, halfway down is the entrance to the council car park containing the mortal remains of King Richard III. The distance between Richard’s original resting place for over 500 years is a mere stone’s throw from his proposed next resting place. Should he be moved a mere few hundred yards into Leicester cathedral? Or should he be moved a hundred miles to be reburied in York?

Looking in the opposite direction: the location of the Greyfriars monastery. Behind the building on the left, halfway down is the entrance to the council car park containing the mortal remains of King Richard III. The distance between Richard’s original resting place for over 500 years is a mere stone’s throw from his proposed next resting place. Should he be moved a mere few hundred yards into Leicester cathedral? Or should he be moved a hundred miles to be reburied in York?

Inside The Car Park. The forbidding green gates, with their modern-day graffeti and barbed-wire tops, .

Inside The Car Park. The forbidding green gates, with their modern-day graffeti and barbed-wire tops, .

The car park is tiny – a lot smaller then it appears on the television. Georgian and Victorian buildings surround the space. With five centuries of urban building-work, it truly is a miracle that the exact location of Richard III’s was left, in the main, undisturbed. At some point during the Victorian period, builders managed to sever the king’s feet as they were not recovered with the remains of the rest of his body in 2012.

The car park is tiny – a lot smaller then it appears on the television. Georgian and Victorian buildings surround the space. With five centuries of urban building-work, it truly is a miracle that the exact location of Richard III’s was left, in the main, undisturbed. At some point during the Victorian period, builders managed to sever the king’s feet as they were not recovered with the remains of the rest of his body in 2012.

A temporary marque protects the grave of the five-hundred years dead king. The building in the background is Alderman Newton’s grammar school, which will eventually become part of the new Richard III Visitors’ Centre. If this building had been built even 50 yards further forward, then we would have lost Richard’s grave forever.

A temporary marque protects the grave of the five-hundred years dead king. The building in the background is Alderman Newton’s grammar school, which will eventually become part of the new Richard III Visitors’ Centre. If this building had been built even 50 yards further forward, then we would have lost Richard’s grave forever.

The grave of King Richard III, the last of the Plantagenets. The only king of England to die in battle, since Harold died in a hale of arrows in 1066. Stripped naked and buried without a shroud, with his hands tied after death, Richard was stuffed into a shallow grave which was too short for him.

The grave of King Richard III, the last of the Plantagenets. The only king of England to die in battle, since Harold died in a hale of arrows in 1066. Stripped naked and buried without a shroud, with his hands tied after death, Richard was stuffed into a shallow grave which was too short for him.

Seeing Richard’s grave was spine-tingling – we so nearly lost him forever to urban development. Eventually the site of his original grave will become part of a beautiful garden next to the new Visitors’ Centre. However, seeing the grave in the setting of a stark and bare council car park was an experience I will never forget.

Seeing Richard’s grave was spine-tingling – we so nearly lost him forever to urban development. Eventually the site of his original grave will become part of a beautiful garden next to the new Visitors’ Centre. However, seeing the grave in the setting of a stark and bare council car park was an experience I will never forget.

The quiet serenity and beauty of Leicester Cathedral. Will this be Richard’s final resting place?

The quiet serenity and beauty of Leicester Cathedral. Will this be Richard’s final resting place?

Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Born 2nd October 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire; died 22nd August 1485, Bosworth Field, Leicester.

Richard, Duke of Gloucester. Born 2nd October 1452 at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire; died 22nd August 1485, Bosworth Field, Leicester.

King of England 1483-1485. Buried 1485 to 2012 in Greyfriars monastery, Leicester.

His current location is known only by the University of Leicester.

What do you think about the search and discovery of Richard III?

Where should his final resting place be?

Please do leave your thoughts in the Comments box below.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

Notes

Images from the British Library’s collection of Medieval Manuscripts are marked as being Public Domain Images and therefore free of all copyright restrictions in accordance with the British Library’s Reuse Guidance Notes for the Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

You may also be interested in the following posts

– Richard III – ‘I am a villain: yet I lie. I am not’

– School Trip Friday – Of cabbages and kings

– Shakespeare’s version of King Richard III

– Richard III lyth buryed at Leicester

– Elizabeth of York

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

Elizabeth Woodville, queen of Edward IV, and their five daughters (left to right) Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Catherine, and Mary. Royal Window, Northwest Transept, Canterbury Cathedral.

Elizabeth Woodville, queen of Edward IV, and their five daughters (left to right) Elizabeth, Cecily, Anne, Catherine, and Mary. Royal Window, Northwest Transept, Canterbury Cathedral. Cigarette card from Ogden’s Guinea Gold series, published 1903.

Cigarette card from Ogden’s Guinea Gold series, published 1903. Cigarette card from Player’s Kings and Queens, published 1935.

Cigarette card from Player’s Kings and Queens, published 1935.

Postcard of the

Postcard of the  Funeral effigy of Elizabeth (plate from 1914)

Funeral effigy of Elizabeth (plate from 1914) Chapel of Henry VII and his queen, Elizabeth of York

Chapel of Henry VII and his queen, Elizabeth of York

Tuck’s postcard Richard III from Kings and Queens circa 1902

Tuck’s postcard Richard III from Kings and Queens circa 1902

Natale d[omi]ni Henrici filij Emundi comitis Richemondie ac d[omi]ne M[ar]rgarete vxoris sui filie Joh[ann]is nup[er] duc[?is] Somersete anno d[omi]ni millio cccc quinquagesimo sexto. Born Henry son of the Earl of Richmond and Margaret his wife daughter of John, Duke of Somerset 1456. (Latin text kindly transcribed by Rob Ellis of

Natale d[omi]ni Henrici filij Emundi comitis Richemondie ac d[omi]ne M[ar]rgarete vxoris sui filie Joh[ann]is nup[er] duc[?is] Somersete anno d[omi]ni millio cccc quinquagesimo sexto. Born Henry son of the Earl of Richmond and Margaret his wife daughter of John, Duke of Somerset 1456. (Latin text kindly transcribed by Rob Ellis of  The xxviijth [28th] daie of January deceassd the noble prynce Henry the eight the yere of owr lorde 1546.

The xxviijth [28th] daie of January deceassd the noble prynce Henry the eight the yere of owr lorde 1546.