Great Dunmow’s local history: Henry VIII’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy Tax

The post Tudor vicar William Walton’s arrival in Great Dunmow explained how one of the drivers for the 1525-6 collection for the church steeple (and the establishment of the beautiful leather account-book), was the arrival of the new vicar, Master William Walton. Another driver for the parish collection must have been the tax imposed by Henry VIII two years prior to the church steeple collection. This tax, known as the Lay Subsidy, was imposed on England by the king to levy money for his expensive wars with France.

Tent design for the 1520 Field of Cloth of Gold (Henry VIII’s meeting with the king of France) (1)

Each village, town and parish throughout England had to keep meticulous records as to the amount that had been levied on each head-of-household. The tax levied was based on a person’s income from their land or moveable good. John Josselyn, from the nearby parish of High Roding, who also owned a manor within Great Dunmow(2), was responsible for collecting the tax within the Hundred of Dunmow.(3) It is possible that the elite and clergy of Great Dunmow, who probably helped Josselyn administer the parish’s 1523-4 collection of the Lay Subsidy, used methods from this tax’s administration to facilitate their own parish collection in 1525-6.

The returns for Great Dunmow’s 1523-4 Lay Subsidy are in The National Archives (T.N.A.).(4) These returns detail a) the house-holder’s name (first name and surname), b) whether they had been assessed for income based on goods or land, c) the Valor (value assessed), and d) the tax payable. These returns would have been written down and recorded by John Josselyn or one of his men, resulting in the detailed manuscript that is now in the care of the T.N.A. Thus, a list of all the house-holders (and, more importantly, their wealth) could have been made available to vicar Master William Walton when he instigated the collection for the church steeple.

Perhaps, after a service in the church, when the parish clergy, churchwardens and church clerk were collecting each person’s contribution to the church steeple, the returns from the Lay Subsidy were used to assess how much each parishioner should pay towards their new steeple. This would explain the distinct connection between a person’s wealth and the amount they paid to a seemingly voluntary collection. This correlation is demonstrated in the graph below, which illustrates the distribution patterns of amounts paid to the Lay Subsidy compared to the steeple collection: the trends are remarkably similar. According to entries within the churchwarden accounts, the cost of labour per day was 4d, therefore the majority of householders were contributing an amount roughly equal to one day’s pay for both the Lay Subsidy Tax and the church steeple collection.

1523-4 Lay Subsidy versus 1525-6 parish collection

The returns for the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy records 139 tax-payers, whereas just over 160 house-holders were recorded for the 1525-6 church steeple collection. This discrepancy can be accounted for by the exemption of clergy and paupers from the Lay Subsidy. Therefore, allowing for the parish’s four clerics (as detailed in the post Late medieval clergy), and a small number of deaths which might have occurred between the two events, it can be assumed there were approximately 20 paupers within the parish. With a greater number contributing to the parish collection, some of the poorest residents, exempt from Henry VIII’s tax, had paid the parish church’s informal levy. Perhaps, for the paupers, it was for spiritual, pious and religious reasons that money was paid to their church rather than to their lord sovereign, the King.

The elite of the parish have also been examined by comparing their wealth, according to the Lay Subsidy, against their generosity to the church steeple collection. From this comparison, it is apparent that at least five lords of the manors from Great Dunmow’s medieval manors paid the highest contributions. This comparison also confirms the men listed at the start of church steeple collection were the elite and from the upper echelons of Great Dunmow’s society. Eamon Duffy has argued that investing in parish projects was one way in which the elite could establish and promote their place in local society.(5) This self-promotion is apparent in Great Dunmow. The largest contributor to the church steeple collection in 1525-6 was the builder and churchwarden, Thomas Savage, who, at £36s 8d, paid over £1 more then the next closest contribution and, according to the 1523-4 Lay Subsidy, was the tenth wealthiest parishioner. In spite of his wealth and generosity, he was only listed twenty-fourth in the list – his wealth and generous contribution were not enough to push him up the social rank. But, it did win him the contract to assist the building of the church steeple (as documented in a later folio within the churchwarden accounts).

Footnotes

1) Tent design for the Field of Cloth of Gold (1520), shelfmark: Cotton Ms. Augustus III. 18, ©British Library Board.

2) Scott. W.T., Antiquities of an Essex Parish: Or pages from the history of Great Dunmow (1873), p74.

3) Hundred of Dunmow: Calendar of Lay Subsidy Rolls (1523-4), The National Archives, E179/108/161. Essex Record Office also hold a photocopy of these returns (Hundred of Dunmow: Calendar of Lay Subsidy Rolls (1523-4) T/A 427/1/1) but they are a handwritten transcript made by an unknown researcher sometime in the last 30-50 years. Having consulted both versions, I have found that the E.R.O. version has some errors in the transcription of names. Crucially, one of these errors concern the distinction as to whether one inhabitant of Great Dunmow’s surname was ‘Pannell’ or ‘Parnell’. Mr Parnell, resident of Great Dunmow, will be discussed in a later blog.

4) Hundred of Dunmow, The National Archives, E179/108/161.

5) Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England,1400-1580, (2nd Edition, 2005).

Notes about Great Dunmow’s churchwarden accounts

Great Dunmow’s original churchwardens’ accounts (1526-1621) are kept in Essex Record Office (E.R.O.), Chelmsford, Essex, D/P 11/5/1. All digital images of the accounts within this blog appear by courtesy of Essex Record Office and may not be reproduced. Examining these records from this Essex parish gives the modern reader a remarkable view into the lives and times of some of Henry VIII’s subjects and provides an interpretation into the local history of Tudor Great Dunmow.

*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*-*

This blog

If you want to read more from my blog, please do subscribe either by using the Subscribe via Email button top right of my blog, or the button at the very bottom. If you’ve enjoyed reading this post, then please do Like it with the Facebook button and/or leave a comment below.

Thank you for reading this post.

You may also be interested in the following

– Index to each folio in Great Dunmow’s churchwardens’ accounts

– Great Dunmow’s Churchwardens’ accounts: transcripts 1526-1621

– Tudor local history

– Henry VIII’s Lay Subsidy 1523-1524

© Essex Voices Past 2012-2013.

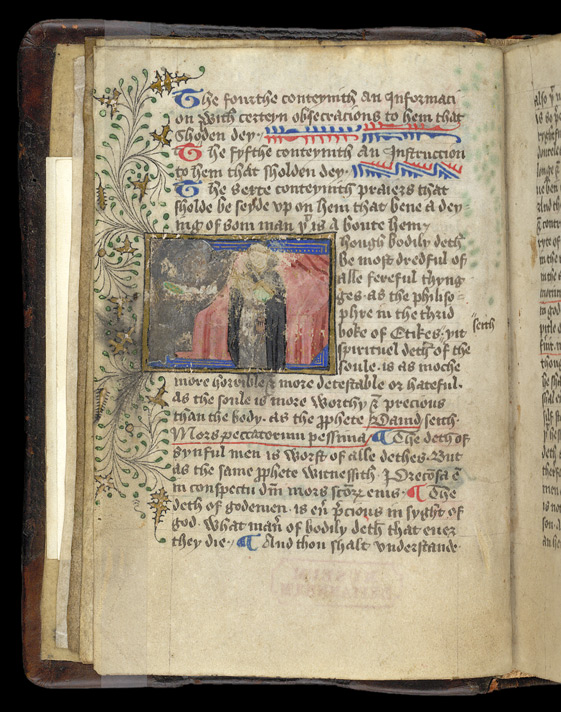

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3).

A Priest Administering the Last Rites(3). A priest giving communion to a sick man,

A priest giving communion to a sick man,